A policy win, an economic hit: Turbulent week reflects Biden’s challenge

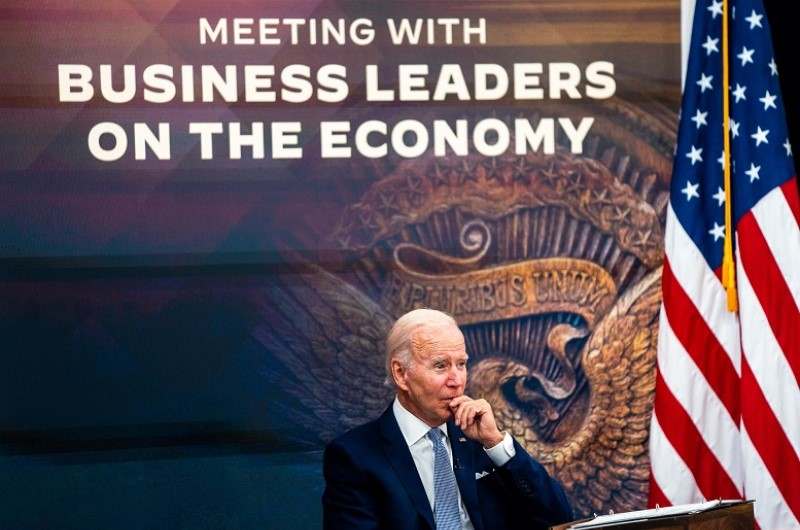

President Joe Biden speaks July 28 during a meeting with CEOs on the economy.

15:28 JST, August 1, 2022

WASHINGTON – President Joe Biden notched a series of unexpected policy wins just hours after emerging from his COVID-19 isolation last Wednesday: Democratic senators announced a startling breakthrough on his long-stalled climate agenda. A multibillion-dollar bill to subsidize computer chip manufacturers was on the cusp of becoming law. And a measure to make some prescription drugs cheaper gained momentum.

But all of that crashed into the news the very next day that the economy contracted for a second straight quarter. Biden and his top aides have spent much of the past few days arguing that the country is not entering a recession, pointing to strong economic indicators such as job growth and low unemployment, but that didn’t stop Republicans from decrying the “Biden recession.”

Now the question becomes whether Biden’s run of legislative wins – particularly if Democrats manage to pass their health-care, climate and clean energy bill, which contains a hugely popular measure to let Medicare negotiate the prices of some drugs – will be enough for Biden to help overcome the stubbornly high inflation that has helped sink his approval ratings.

That question will help define the final two years of Biden’s term. Democrats are at risk of losing their narrow Senate and House majorities in November’s midterm elections, and operatives on both sides say the president’s popularity will be a major factor. If Democrats lose the House, as many analysts expect, Biden is likely to face numerous investigations; if they lose the Senate, Biden will struggle to confirm judges and other appointees. Democrats feel they have a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to pass an ambitious climate agenda given that they hold unified control of Washington and do not know when that will happen again.

Still, the action in Congress has the potential to change the narrative of Biden’s presidency. Until recently, Biden was widely seen to have fallen short of his promise that he could bring the parties together to pass bills that would help Americans. But in his first two years, he has pushed through a coronavirus relief measure, an infrastructure law, a modest gun-control law, a semiconductor law – and now, possibly, a climate and prescription drugs package.

Yet several economists said that package, dubbed the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, will have a modest impact on inflation in the near term. And they expressed skepticism that voters would feel more confident about Biden’s leadership because he has passed a slew of bills when they are struggling with the everyday costs of food and other items.

The Democrats’ package “will help with inflation and make the [Federal Reserve’s] job a little bit easier, but far and away the largest and most important forces in the economy are well outside the control of anything the president or Congress could do,” Jason Furman, who was a top economic adviser to President Barack Obama, said Friday.

It’s not that it won’t make a difference, Furman said – it’s that it won’t happen by the midterms. “Over time, the legislation that was passed this week, and they made progress on this week, will matter much, much more than any of this week’s economic data,” said Furman, now an economics professor at Harvard. “The problem is, that may not be true on a time scale of two months.”

Politically speaking, Democrats say their bill at least allows them to show they are trying to help voters. White House officials say their goal is to draw a stark contrast with Republicans, a mission they say has now become considerably easier.

One White House official stressed that the administration was “being careful not to count chickens before they hatch,” given that the economic bill still must be pushed through Congress, which Democrats are aiming to do using a parliamentary process called reconciliation. The Democratic caucus’s slim majority in the Senate – the chamber is divided 50-50, with Vice President Kamala Harris casting tiebreaking votes – means every Democratic vote is needed, and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema, D-Ariz., has not yet said whether she supports the bill.

Republicans say the economic package will do little to assuage voters regardless.

“Americans know Democrats can’t be trusted,” Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said Thursday on the Senate floor. “They know it every time they fill their gas tank, every time they check out at the supermarket, every time parents stay up late at their kitchen table trying to figure out which bills they can afford to pay this month.”

Republicans plan to frame the economic package as a tax increase, since it includes a provision to make sure large corporations pay a minimum tax. “The Democrats who’ve robbed American families once with inflation now want to rob the country a second time, through gigantic job-killing tax hikes,” McConnell said.

Democrats, for their part, plan to highlight many Republicans’ votes against both the semiconductor bill and another popular measure that would help military veterans who have been exposed to toxic burn pits. Measures providing help to veterans usually have broad bipartisan support, and White House officials felt Republicans handed them a political gift by opposing such a popular bill.

“This week showed the president and congressional Democrats have a plan to lower costs for middle class families,” White House spokesman Andrew Bates said Saturday. “What is congressional Republicans’ plan? Only extreme ideas that would prolong inflation, end Medicare in five years and raise taxes on nearly 100 million working people.” That was a reference to an agenda outlined by Sen. Rick Scott, R-Fla., who heads GOP senators’ campaign arm, though he denies his plan would have those consequences.

Even many Democrats concede privately that while the White House may have little choice but to stress that the country is not in a recession, that is hardly politically desirable turf. Rather than litigate either the economy or the president’s record, some in the party contend, Democrats should be focusing on a message that Republicans are extremists.

Republicans are increasingly out of step with most Americans on hot-button issues including abortion and gun control, these Democrats say, and the GOP has not presented its own plan to deal with inflation and high gas prices, which have fallen considerably in recent weeks.

“Arguing whether we’re in a recession or not is not the economic argument to make. The economic argument you make has to be relevant to people’s lives,” said Joel Benenson, a Democratic strategist and former Obama pollster. “You have to make the case that you are the party that is fighting for working- and middle-class Americans, and Republicans continue to be the party that gives tax breaks to corporations and the super wealthy.”

Presidents have little control over the economy, most economists say, even though the issue historically plays the largest role in whether voters approve of the job a president is doing. Both Republican and Democratic presidents have historically blamed bad economic news on their predecessors or the alternate political party, while taking credit for any positive indicators.

Republicans have hammered Biden on rising fuel prices all year, and gas surpassed $5 a gallon in June for the first time ever. As prices have fallen in recent weeks, Biden and his deputies have repeatedly touted the decline and pointed to the extra money it will put in Americans’ pocketbooks, but so far that message does not appear to be moving voters.

Economists say the measures needed to cool the economy and tamp down inflation – including the Federal Reserve hiking interest rates – are painful to many voters.

“If you’re arguing over the definition of a recession or you’re explaining, you’re losing. They’re just in a really bad place,” said Douglas Holtz-Eakin, a former Congressional Budget Office director who now runs American Action Forum, a conservative think tank. “The inflation picture is getting worse, not better. I think that’s simply going to be more important to people than the definition of a recession or this piece of paper that’s supposed to do something on inflation.”

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 – as the package including climate action, prescription drug negotiations and the minimum corporate tax is officially called – is significantly smaller than the transformative $3 trillion bill Biden initially sought that some Democrats likened to the New Deal. But it would still represent one of the most consequential pieces of economic policy in recent U.S. history.

It would allow Medicare to negotiate the price of some drugs, cap seniors’ out-of-pocket prescription drug costs at $2,000 per year and penalize drugmakers for price hikes above the rate of inflation, making it the most significant drug pricing legislation since 2003.

The Medicare provisions have broad bipartisan support, with more than 90% of Americans saying in a Kaiser Family Foundation poll in March that letting the government negotiate with drug companies to get a lower price on Medicare prescription drugs should be an “important priority” or a “top priority” for Congress.

The measure would also extend Affordable Care Act subsidies for three years, avoiding premium hikes right before the November midterm elections.

The bill also includes the largest investment in fighting climate change in U.S. history, aiming to boost clean-energy technology even as it delivers some of the support that Sen. Joe Manchin, D-W.Va., sought for fossil fuels. To cover its costs, the bill looks to bolster the Internal Revenue Service’s ability to pursue tax cheats, in addition to the minimum tax that targets profitable companies that pay nothing to the U.S. government. And it raises more than $300 billion that can be used to reduce the federal deficit.

Biden and other White House officials have repeatedly cited economists who have said the bill would help reduce inflation. They have leaned heavily on comments from Larry Summers, a former treasury secretary who had been warning about inflation for a year and helped assuage Manchin’s concerns. Summers said the bill was “an important step forward on inflation.”

Even so, some economists have said the bill’s effects on inflation will take years. The drug pricing and climate provisions will appeal to Democrats’ base but may not make a significant dent with upset voters worried about how they will afford their bills in the coming weeks and months, said Stephen Miran, who served as a senior official in the Treasury Department in the Trump administration and is the co-founder of Amberwave Partners, an investment fund.

“I think that everyone knows that President Biden and the Democrats are concerned about inflation,” Miran said. “They talk about it enough. [But] I don’t think many people are convinced they’re doing anything meaningful to stop inflation.”

The Inflation Reduction Act “will do good work in consolidating President Biden’s own coalition behind him, but they were very likely to support him anyway,” Miran added. “In respect to the real political problem, which is middle-class households dealing with record inflation, I don’t think this is going to move the needle.”

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

JN ACCESS RANKING