Biden, FEMA head to Florida as survivors scramble for federal aid

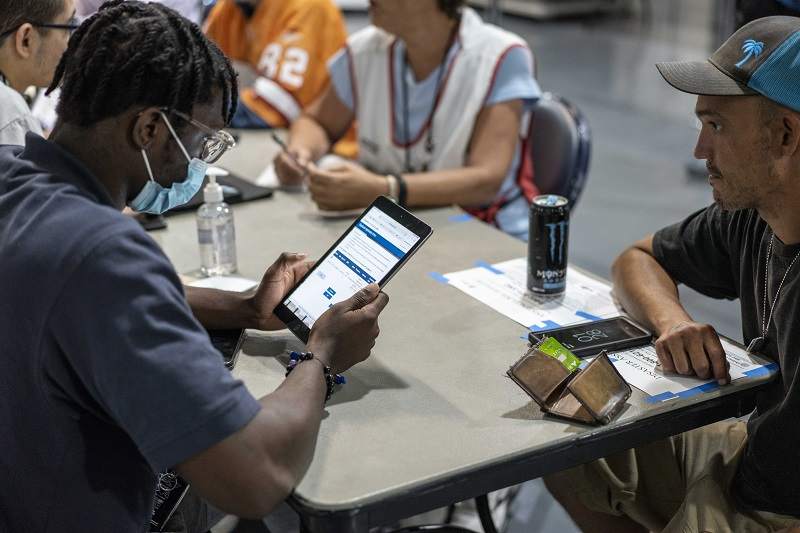

FEMA representatives take information from displaced people at Hertz Arena.

15:40 JST, October 5, 2022

ESTERO, Fla. – Shirley Silva left the flooded home she’s been living in with family members since Hurricane Ian struck last week and drove to a shelter on Monday, hoping to get some help from the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Instead of immediate assistance, she faced delays.

At a crowded FEMA registration table, a staffer told Silva, 62, to call a hotline she had already tried, waiting on hold for nine hours.

“I can’t do that again,” said Silva, a retired caregiver who years ago had taken in three children of a relative. “We desperately need a place.”

As President Biden and FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell prepared to visit storm-ravaged Fort Myers, Fla., and meet with Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) on Wednesday, a week after the hurricane hit, many survivors said they were still struggling with basic needs.

The Florida Medical Examiners Commission has confirmed 72 storm-related deaths, but the toll is likely higher: County sheriffs have documented additional deaths not included in that total and searches continue for the missing.

Over 200,000 individuals had applied for FEMA assistance early Tuesday, according to Florida Division of Emergency Management. Of those, about 99,000 had been approved, for a total of about $73 million in individual assistance, the agency said.

Yet residents with limited transportation and internet access said it was difficult to figure out where to get immediate help with food and housing.

Some who applied for FEMA assistance at the shelter said FEMA staff referred them to the American Red Cross for temporary housing assistance, although the agency was referring hurricane survivors back to FEMA, a Red Cross spokeswoman said.

“We’re trying to get a hotel from FEMA, but we really didn’t get too far on that,” Silva said as she left the shelter. She’d brought her two boys with her, ages 13 and 16. The 13 year-old piped up.

“The inspector’s coming!” he said, referring to a FEMA pledge to inspect her home. Silva sighed.

“The inspector won’t be here for seven to 10 days,” she said.

The storm not only flooded her house, it also ripped off swaths of her roof. The FEMA staffer put her on a list to receive tarps to patch the damage, but couldn’t say how soon those would arrive.

“I’m in limbo right now, an uncertain world. I just want to find shelter because it’s not good for your lungs,” she said of the damp house, alluding to health issues suffered by the children. “They have to do something. We will be homeless and I fought hard to keep three children together and out of state care.”

Last Friday, Congress approved a stopgap spending measure that allows FEMA to tap $19 billion to respond to Ian and other disasters. All 16 of Florida’s Republican House members opposed the bill.

Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.) voted against the spending bill; Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) was in Florida and missed the vote. Both have said they opposed Democrats tying disaster relief to unrelated spending, and on Friday they sent a joint letter to the Senate Appropriations Committee asking for funding to “provide much needed assistance to Florida.”

Federal assistance is supposed to be available to hurricane survivors across southwest Florida, officials said. Those grants are supposed to help pay for temporary housing, emergency home repairs, uninsured and underinsured personal property losses or medical, dental and funeral expenses related to the disaster, and applicants are reviewed on a case-by-case basis to determine need, officials said.

“We’re aware of the unique needs communities impacted by Hurricane Ian are experiencing and our disaster survivor assistance teams are being sent to these areas because we believe in meeting people where they are,” said Jaclyn Rothenberg, FEMA director of public affairs.

Chauncia Willis, CEO of the Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management, said her group was working with FEMA – calling to check on residents in Fort Myers’s historically Black Dunbar neighborhood on Tuesday, while also contacting other underserved communities, such as migrant farmers and immigrants. Many are non-English speakers now living without power, she said, which makes it more difficult to apply for FEMA aid.

“They cannot access those applications and they need immediate support,” Willis said.

DeSantis announced Tuesday that the state’s first disaster recovery center had opened in Fort Myers, staffed by FEMA and other federal and state emergency response agencies, and that more would be opening in coming days.

Nearly 3,000 people impacted by the storm were staying at 22 shelters Tuesday, and that number rose in recent days as some discovered their homes were unlivable, ran out alternative places to stay orcouldn’t afford staying at a hotel, said Brad Kieserman, vice president of disaster cycles services for the American Red Cross.

Kieserman said he expects storm shelters to remain open for at least six months.

“Trying to find stable, affordable housing, especially for people who have been displaced and may not be eligible for federal housing, is very difficult,” he said.

As Silva left the shelter, June Gonzalez stood nearby, preparing to head to work. Before the storm, Gonzalez, 44, evacuated to the shelter from her mobile home on Pine Island with her fiance and 12 year-old son, Luis Andrietta, who is autistic and has to stay out of the heat due to a health condition.

Neighbors told Gonzalez that Hurricane Ian destroyed her rented trailer. So she stayed with her family at the shelter, showering at her boss’s house and reporting to work as manager of a Denny’s in nearby Cape Coral, where her fiance works maintenance. Her son will only eat certain foods, which she had to buy or bring him from work.

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Gonzalez said, having checked with FEMA staff at the shelter. “They said I probably won’t even get assistance because we’re renters, not owners. I don’t count on any help from them.”

She applied for FEMA assistance the day after the storm, but hadn’t heard from anyone. She said her sister in Puerto Rico received FEMA assistance after Hurricane Maria and told her to be patient, that “it’s a process, it takes time.”

Hundreds of people and their pets filled the hallways at Hertz Arena, which is being used as a shelter. Gonzalez would prefer to stay at a hotel, but rooms are scarce, prices spiking and none of the agencies at the shelter were offering temporary housing assistance. She said her friend was paying $241 per night, money that Gonzalez needs for food.

Pat Helland, 80, a retired customer service worker, evacuated to the shelter from her flooded home on Sanibel Island and wasn’t sure how to apply for FEMA assistance. She didn’t have a computer or phone and needed nurses to bring her a wheelchair just to get to the shelter’s FEMA desk. Helland said she had always relied on her husband to take care of their house, but he died a year and a half ago.

“FEMA was here, I think they’re coming tomorrow. What am I going to do? This is a big place,” Helland said as she sat on her cot next to the cage of her pet parrot, Will.

Nina Marshall also found the process of applying for FEMA aid confusing. Marshall, 56, had been living with her 88-year-old mother in her duplex in Fort Myers when the hurricane struck. Her mother applied for FEMA help, but when Marshall tried at the shelter, FEMA staff told her she was already part of her mother’s application and would have to wait for that to be processed, including potentially a low-interest federal loan for her dog-sitting business.

Marshall didn’t like the idea of taking out another loan.

“I don’t know – I already have a lot of debt,” she said.

The American Red Cross took over the Hertz Arena shelter this week from the county, and along with other organizations was trying to assist residents. Groups like the Naples-based nonprofit Better Together distributed food, diapers and first-aid kits in the Harlem Heights neighborhood of Fort Myers, a mostly Black and Latino neighborhood that was among the hardest hit by the hurricane, where residents were still living in flooded homes and struggling for basic necessities.

FEMA search and rescue teams, meantime, walked the streets still brimming with knee-deep storm water, checking on residents.

“You guys okay?” shouted a team member from Montgomery County, Md.

“Yeah, we’re fine. But we don’t know what to do – this is our first disaster,” said Adriana Harvey, sitting on the porch of her family’s flooded home in rain boots.

Harvey asked about assistance to repair her home. Before the storm, she had received a notice from her mortgage company that she had to buy flood insurance, which she did – her bank showed the check for about $2,500 cleared – but did that mean she was covered?

“I can’t tell you anything about insurance,” said the search and rescue team member, Jeffrey Taylor. “Try to take everything out. If you want to do any kind of work in there, wear a mask. It’s going to get worse.”

Adriana Harvey of Harlem Heights, with husband Jose Cruz, right, and son Jose Cruz Jr., left, talking to a search and rescue officer from Montgomery County, Md., outside their home.

Harvey, 32, a house cleaner, has been living at home since the storm with her 13-year-old son and husband, a roofer who’s already back at work, using their one remaining car. Their three other children were staying with her sister in nearby Lehigh Acres, but Harvey wasn’t sure how long that would last. And she wasn’t sure if they should return to the house. Not only had water seeped into the floor, all of the food in their refrigerator had spoiled.

Across the street, Gladiolus Food Pantry also lost a walk-in freezer full of food, the remains piled in dozens of trash bags out front. Founder Miriam Ortiz’s home behind the pantry, built by Habitat for Humanity, also flooded. But that didn’t stop Ortiz and other volunteers from gathering donations to feed hurricane survivors this week, about a thousand a day.

Miriam Ortiz, left, is the founder and director of Gladiolus Food Pantry in Harlem Heights, Fla.

Ortiz, who moved to Harlem Heights from Mexico 25 years ago, wasn’t sure she could sustain that level of support. Before the storm, she was supplying 850 families a month.

“That’s why I can’t sleep at night,” Ortiz said. “Imagine how many will be coming now. I really need help.”

Anita Parmer was volunteering at the pantry this week after the storm destroyed her home on Fort Myers Beach. Parmer, a retired elementary school teacher for special needs students, evacuated to a friend’s house in Naples before the storm and was still staying there. Fire officials hadn’t allowed her and other evacuees to return, although a friend sent her cellphone video showing extensive wind and flood damage. Her monthly mortgage payment is due soon.

“I registered with FEMA; they said an adjuster would be out. He called me this week, and I have to tell him you can’t get on the island,” said a frustrated Parmer, 68. “If I can’t get in there, how am I going to tell you what’s damaged? Is it salvageable? After two weeks being closed up, will anything be salvageable?”

Among those picking up donated jambalaya, water and a bag of groceries at the pantry was Gary Pierre Louis, 46, who brought his wife and 5-year-old son. Pierre Louis works advising migrants on their paperwork, and said he doesn’t want to leave the area because he has clients to help.

But his rented townhouse in the Island Village neighborhood and his office flooded. He had rental insurance and applied to FEMA but wasn’t optimistic they would help, having applied after his former rental was damaged by Hurricane Irma in 2017.

“They came, they took pictures of the house and six months later, nothing happened,” he said, until he pressured insurers to make the repairs.

FEMA officials said they were sending teams to the area this week.

On Tuesday, FEMA inspectors visited nearby Pine Ridge Palms mobile home park, owned by residents ages 55 and up.

Jim Anderson, 73, a resident who works maintenance at the park, was making repairs himself, since he didn’t have insurance. He planned to apply for FEMA assistance, but worried what it would provide.

Standing outside his home, surrounded by twisted sheet metal debris, Anderson recalled how a neighbor had applied for a replacement trailer from FEMA after Hurricane Irma hit in 2017. When it finally arrived in June – nearly five years later – it was the wrong size for the lot, he said, and cheaply made, with the door on the wrong side.

His wife, Mikim Anderson, 63, who works at Walgreens, suggested they might get help from local government. But her husband insisted, “The only people I know of who can help us is FEMA because they have the money.”

Of the park’s 205 properties, resident Liz Lewis had figured up to 40 were a total loss, including her own. Then she and her husband, David Lewis, president of the homeowners’ association, talked to FEMA inspectors on Tuesday and realized that was a gross underestimate.

“There is going to be many more than that that they are probably going to condemn,” Lewis said. “They told us anyone who had flooding above the flooring will be a teardown. It’s going to be a lot.”

Volunteers and staff members with Better Together, a nonprofit organization based in Naples, Fla., deliver food and toiletries for families in the Harlem Heights neighborhood in Fort Myers, Fla., on Tuesday.

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

JN ACCESS RANKING