Rolando Cubela, who plotted with CIA to kill Cuba’s Castro, dies at 89

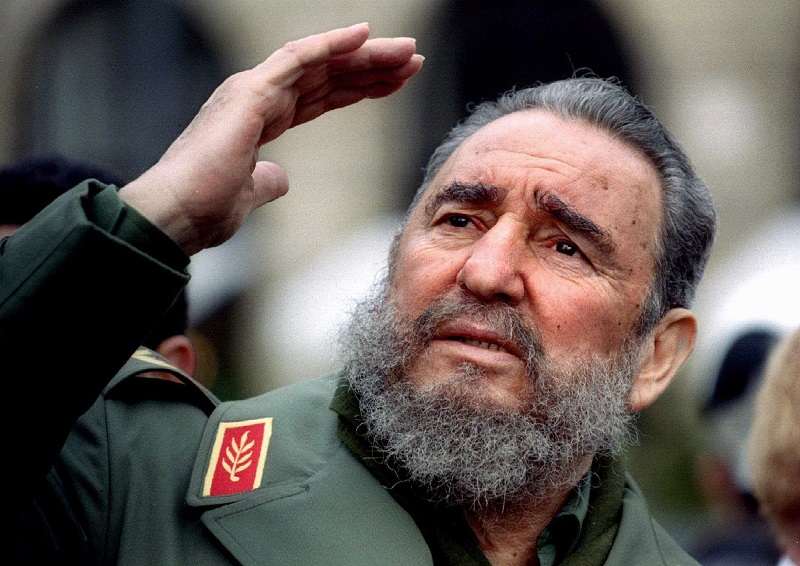

Cuba’s President Fidel Castro gestures during a tour of Paris in this March 15, 1995 file photo.

12:07 JST, October 9, 2022

In March 1966, Rolando Cubela stood before a Havana military tribunal accused of leading a plot to kill his former comrade, Fidel Castro. During the two-day proceedings, Cubela never denied he sought to assassinate Cuba’s “maximum leader,” but reportedly blamed himself for falling “into the hands of the enemy.”

That contrition, carried by Cuba’s state-controlled media, gave Castro what he needed. Sending Cubela and four other convicted plotters to face firing squads could have created powerful martyrs to further rally opponents of his rule. Instead, Castro made a public display of saying he wouldn’t condemn Cubela and other former allies to death.

Cubela, who died Aug. 23 in Doral, Fla., at 89, would spend the next 13 years in prison – closing one of the more intrigue-filled footnotes from the turbulent years after Castro’s guerrillas overthrew Fulgencio Batista’s U.S.-friendly regime in 1959.

Cubela’s path to a Havana jail cell included clandestine meetings with CIA operatives in Europe, code names, ideas to kill Castro including a poison-filled pen and suspicions that Cubela may have been playing both sides as a double agent, according to declassified U.S. documents.

Cubela’s turn against Castro was a particularly harsh blow for the Cuban leader. During the revolution, an alliance between Castro’s guerrillas and factions led by Cubela avoided rivalries among anti-Batista forces and proved pivotal in critical battles against government troops in the final months, said Arturo Lopez-Levy, a research fellow at the University of Denver Korbel School’s Latin America Center.

“It’s a hard thing to say if Cubela was seriously plotting to kill Castro, but if someone could have done it, it might have been Cubela,” he said.

Cubela, who studied medicine in Havana, gained prominence in stunning fashion: taking part in the slaying of a top military intelligence officer, Col. Antonio Blanco Rico, in a Havana nightclub in October 1956.

The next year, members of Cubela’s group, known as the Student Revolutionary Directorate, or DRE, tried to storm Batista’s presidential palace, but were driven back after clashes left heavy casualties on both sides. DRE co-founder José Echeverría was killed in a simultaneous attack on a radio station in Havana.

Fearing arrest, Cubela stowed away on a merchant ship bound for Florida. He returned to Cuba by boat in February 1958, later uniting the Directorate units with Castro in a pivotal win over government troops that December. Batista fled Cuba on New Year’s Day 1959.

Cubela was solidly in Castro’s inner circle after he took power. He proudly displayed a long scar, from right shoulder to biceps, from an injury during fighting. Yet, as Castro consolidated control, Cubela became increasingly dismayed by his embrace of communism and strongman rule.

A 1967 Inspector General’s report on plots to assassinate Castro, released to the public in 1998, sketched out Cubela’s overtures to the CIA and then his deepening involvement in covert planning, given the cryptonym “Amlash.”

A January 1965 CIA memo, released as part of the Inspector General’s report, called Cubela “a representative of an internal military dissident group, which is plotting to overthrow Castro.”

In July 1962 – with the Kennedy administration still reeling from the failed Bay of Pigs invasion in 1961 – Cubela met with CIA contacts at a Helsinki nightclub. Cubela agreed to stay in Cuba to “carry on the fight there,” the Inspector General’s report said. His demand in return: to be “given a really large role to play” if Castro was removed. Cubela received clandestine training at a CIA safe house in France.

In the fall of 1963, Cubela was in Paris as a new CIA plot was hatched – possibly having Cubela use a ballpoint pen filled with a toxic alkaloid known as Black Leaf 40 delivered through an ultrafine syringe, the report said. There was an urgency in Washington’s covert teams. Earlier ideas to strike at Castro, including using mobster hit men or poison cigars, fell apart.

Shortly after Cubela examined the pen on Nov. 22, 1963, they learned that President John F. Kennedy had been shot in Dallas. “Cubela was visibly moved,” the report said, “and asked ‘Why do such things happen to good people?’ ” The pen plot was scrapped.

Cubela wanted weapons, including a sniper rifle with a scope and silencer, the report said. The CIA arranged for Cubela to meet in Madrid in 1964 with Manuel Artíme, a leading anti-Castro militant based in the United States. Artíme agreed to provide the rifle and a handgun, which Cubela managed to smuggle back into Cuba in early 1965.

Soon, however, rumors began to circulate in Cuba about brewing conspiracies against Castro. The CIA ended ties with Cubela for “security reasons,” Brian Latell wrote in his 2012 book, “Castro’s Secrets: The CIA and Cuba’s Intelligence Machine.”

The break raised suspicions that Cubela could be under Cuban surveillance or working as a double agent, spilling information to people in Castro’s regime to gain favor or try to build his network for a post-Castro leadership.

For years, the CIA had been wary of Cubela after he refused to take a polygraph test, the Inspector General’s report said. Artíme also was seen as a wild card, the Inspector General’s report said. National security adviser McGeorge Bundy “concurred that Artíme was a firecracker in our midst,” a memo said.

In a tape of Castro remarks played in 1978 before a House committee, the Cuban leader said Cubela was tried and sentenced “for the plots against our lives,” but declared that he had not known of Cubela’s CIA backing until the Senate’s investigations.

On Feb. 28, 1966, Cubela was arrested in Havana. At the same time, Cuban secret police were rounding up others who would join Cubela at trial, including Ramon Guin Diaz, another former top commander in Castro’s forces.

At the trial, Cubela portrayed himself as falling into personal turmoil and self-harming indulgence. (A previously classified U.S. document said Cubela “reportedly likes drinking, loves jokes, and is social, amicable and friendly.”)

“I was carrying around a series of preoccupations and contradictions, the product of long struggle after the triumph of the revolution,” he told the court, saying he led “a disorderly life, a life of parties, cabarets, a completely insane life. I was decomposing and deteriorating.”

Released in 1979

Rolando Cubela Secades was born in Cienfuegos, Cuba, on Jan. 19, 1933, and was active in student affairs during his medical studies in Havana. He joined the Student Revolutionary Directorate after Batista took power in a military coup in 1952.

Cubela was released from prison in August 1979 as part of an agreement with the Carter administration that freed thousands of political detainees in Cuba. Cubela moved to Madrid, where he worked as a cardiologist and took part in several rallies calling for greater freedoms in Cuba. He moved to Miami after retirement.

His death was announced in a Facebook post by Alfredo Fernández-Gamez, a prominent member of the Cuban American community in South Florida and a friend of Cubela. Cubacute, a Spanish language news site in Miami, said Cubela’s sister, Caridad Cubela Secades, told the Spanish news agency EFE that Cubela died in a hospital in Doral, Fla., of respiratory problems. Complete information on survivors was not immediately available.

The Inspector General’s report said none of Cubela’s “dealings with the CIA from March 1961 until November 1964 were mentioned in the trial,” with the evidence focused on Cubela’s meetings with Artíme.

“If the full details of Cubela’s involvement with CIA had come out in court,” the report continued, “Castro might have had little excuse for asking for leniency.”

"News Services" POPULAR ARTICLE

JN ACCESS RANKING