Spotlight shines on poet Chika Sagawa decades after early death at 24

Chika Sagawa

10:57 JST, August 11, 2022

As a rising star in the early years of the Showa era (1926-89), Chika Sagawa’s passing at the young age of 24 would later earn her the moniker of “the phantom poet” since her works were so hard to find.

Now, over eight decades after her death in 1936, Sagawa’s works are being rediscovered by the literary world. A collection of poems published in April is selling surprisingly well, and some poems that were translated into other languages have caused a stir overseas.

Born in Hokkaido in 1911, Sagawa ventured to Tokyo after graduating from a secondary school for girls in Otaru. She excelled in English and, in addition to translating James Joyce’s collection of poems titled “Chamber Music,” she composed surrealistic poems inspired by the modernism movement that emerged in Tokyo following the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923. She was hailed as an artist with a bright future, but stomach cancer brought her life to a premature end.

The recently released collection of her works was edited by Ryu Shimada, a researcher at Ritsumeikan University’s Institute of Humanities, Human and Social Sciences. He assembled an assortment of Sagawa’s poems, translations, written prose, journal entries and letters.

“At a time that proletarian literature was quite the rage, she can be credited with the great achievement of proactively introducing poetry and criticism by overseas authors together with Sei Ito and others as an advocate of modernism,” Shimada said.

The collection has already sold 7,000 copies, an unusually large figure for a book of poetry.

“Intrinsic in Sagawa’s poems are elements of the hardship and solitude experienced by women, which is what likely makes them also appealing to modern readers,” Shimada explained. In fact, her poems are filled with an allure that breaks through eras.

“Subete no mono ga choshoshiteiru toki Yoru wa sude ni watashi no te no naka ni ita.”

(While everything sneered The night was already in my hands.)

— From “Sabita Naifu” (The rusty knife)

“In the background of Sagawa’s creative work was translation,” Shimada said. “Ito, who was from the same region, wrote lyrical poems following traditions dating from the Meiji era (1868-1912). But Sagawa spurned tradition. Stimulated by the likes of Virginia Woolf, Joyce and others and absorbing the urban culture of the times in Otaru and Tokyo, she created cutting-edge poems.”

“She started doing translations as a teenager. She had a different degree of precociousness,” he added in praise of one who produced such a rich collection of writing in such a short life.

Her poems were never published in her lifetime. And because a collection of her works published posthumously was soon only available at stiff prices at secondhand book stores, she was long regarded as “the phantom poet.”

The recent publication of the collection of her complete works has caused a resurgence of interest in Sagawa, as clerks in bookstores who are fans of her put her book on special displays. A selection of her poems has been translated into English, Spanish and other languages, drawing praise overseas.

“As a researcher, I find it nothing but amazing,” Shimada said.

Resurrecting other female poets

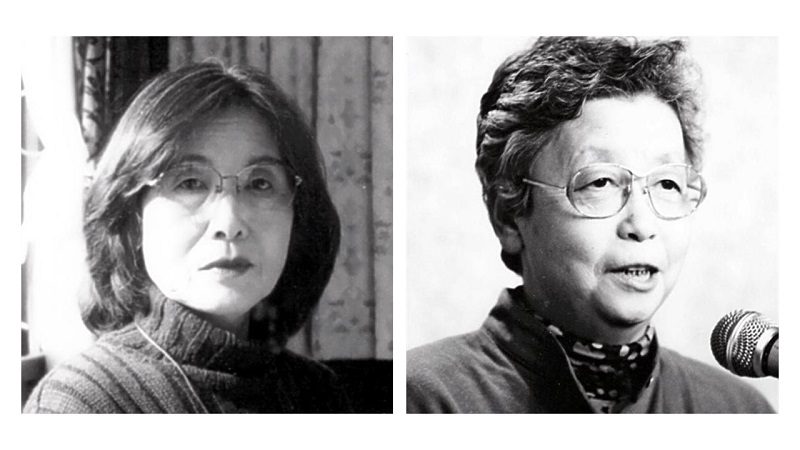

The complete collections of works by Toyomi Arai and Keiko Mure, two women poets who died the same year a decade ago, were published simultaneously in January.

Toyomi Arai, left, Keiko Mure

Arai (1935-2012), a highly regarded poet who won the Jun Takami poetry award with her “Yoru no Kudamono” (Fruits of the night), also made a name for herself through her research on fellow women poets. Her “Kindai Josei Shi o Yomu” (Reading modern poetry by women) is a compilation of her study on Japanese women poets in modern times.

Mure (1929-2012) participated in the poetry magazine Arechi launched by Nobuo Ayukawa, Ryuichi Tamura and others. Beside writing poetry, she studied Ayukawa’s works, making this research her life’s mission and leaving a book on the subject.

Noriko Ibaragi

Another woman poet whose popularity is rising is Noriko Ibaragi (1926-2006). This year has seen the sixth reprint of Bessatsu Taiyo magazine’s special issue on the poet published by Heibonsha, and Bungei Bessatsu magazine, published by Kawade Shobo Shinsha, also released an expanded and updated version of its special issue in May.

“Ibaragi did not just use poetry to express her own feelings, she also had a strong interest in the power of words,” said critic Eisuke Wakamatsu, who wrote a book on the subject published by NHK Publishing, Inc.

Commenting further on why women poets have been brought into the spotlight of late, Wakamatsu said, “In times of upheaval, as we lose sight of the origin of life, the foundation of life, it may be inevitable that the words of these poets are resurrected.”