Reviving the joys of learning history through manga

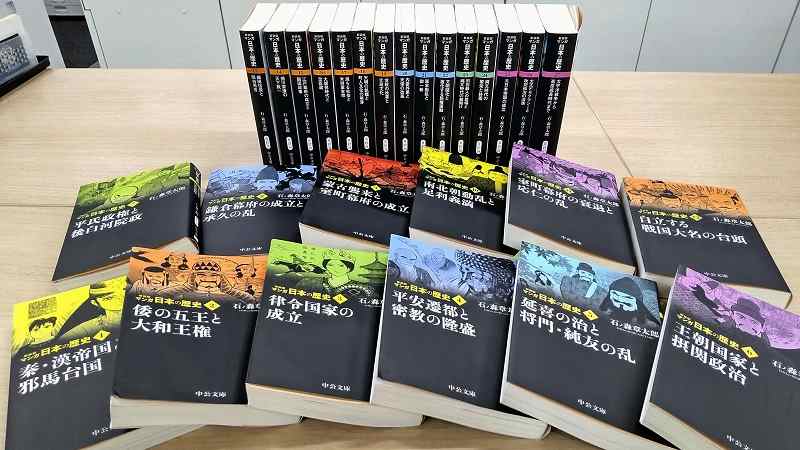

Shotaro Ishinomori’s 27-volume “Manga Nihon no Rekishi,” the final volume of which was published in June

12:02 JST, August 11, 2022

Shotaro Ishinomori (1938-98) has long been lauded as one of the leading managaka in Japan. Among his most notable works is “Manga Nihon no Rekishi” (History of Japan in manga), which was published twice from 1989-99, first as a series of hardcover volumes, and then in paperback. Recently, Chuko Bunko of Chuokoron-Shinsha, Inc. revamped the work into a 27-volume compilation featuring new cover designs, with the final volume published in June.

Ishinomori based his creation on research provided by well-known historians, and the work is highly regarded as a landmark in the historical manga genre. Now the latest edition is attracting and exciting history fans, old and new alike.

Ishinomori was known for his groundbreaking work in the realm of business comics, crafting such titles as “Manga Nihon Keizai Nyumon” (Introduction to the Japanese economy in manga). Nevertheless, then publisher Chuokoron-sha — the predecessor of Chuokoron-Shinsha — apparently thought it would be difficult to depict Japanese history in manga form.

Ishinomori wrote: “In making this manga into something I can proudly call my life’s work, I’m struggling to [combine] imagination — the greatest weapon in the manga genre — and mountains of academic reference materials.”

Other companies had published history-based manga, but those works primarily targeted elementary and junior high school students. The “Manga Nihon no Rekishi” series, however, skillfully portrayed people who appealed to both children and adults.

Ishinomori interpreted historical figures in his own way, portraying each as a fascinating character. Examples include Himiko, who ruled an ancient country called Yamatai-koku in what is now Japan with transcendent divinity and charisma, and feudal lord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who won the hearts and minds of the people with a mix of cruelty and generosity.

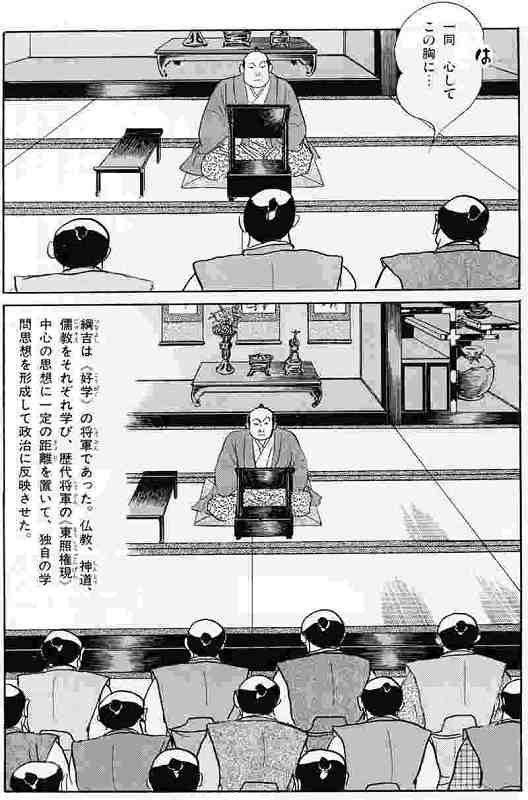

Ishinomori’s manga was founded upon a rigorously researched draft prepared by historians. “Ishinomori insisted that we show him historical documents to ensure his narrative was evidence-based,” recalled draft co-author Toshihiko Takano, professor emeritus of early modern history at Gakushuin University.

The draft incorporated the most up-to-date theories of the time. For example, the Edo period (1603-1867) shogunate is said to have adopted a policy of national seclusion, forbidding Japanese citizens from traveling overseas and foreign nationals from entering Japan. But it was discovered that trade and diplomacy was allowed through four channels: Between Nagasaki and the West or China; Tsushima Island and the Korean Peninsula; the Satsuma domain in today’s Kagoshima Prefecture, and the Ryukyu Kingdom, which ruled Okinawa for centuries; and the indigenous Ainu people in Hokkaido and the Matsumae domain also on the northern island.

A law prohibiting cruelty to animals, which was regarded as a symbol of Tokugawa Tsunayoshi’s (1646-1709) misrule, is now being reevaluated as a key policy that changed how people of the time thought. Values emphasizing military strength had been in place since the Sengoku (warring states) period in the 15th and 16th centuries, when killing was a daily occurrence.

The latest edition of Ishinomori’s work incorporates a newly added explanatory section, which includes recent theories and changes in historical perception. For example, a theory emerged in the 2000s positing that the Yayoi period (300 B.C.-A.D. 300) may have begun 500 years earlier than generally believed. There also is an explanation about the growing tendency to regard the period from the Manchurian Incident to the end of World War II as two different wars started for different reasons, rather than a continuous “15-year war.”

There are many cases in which cutting-edge theories introduced by the manga 30 years ago have been incorporated into textbooks as established theories.

“There were some concerns that adapting history into a manga format could deprive people of the ability to think [for themselves] about history based on the written word, and might somehow provide them with false images of the past,” Takano said. “But it was meaningful to provide the results of historical studies at a time when young people were becoming less interested in reading. We hope the series will be read by junior high and high school students and those preparing for school entrance exams, as well as older generations who are relearning history.”

An excerpt from “Manga Nihon no Rekishi 16: Daikaihatsu Jidai to Chushingura”(History of Japan in manga 16:An era of great development and the revenge of the 47 ronin)