Kachidoki bridge rises again in diorama form

Two preserved sets of power generating equipment, which were used to convert alternating current provided by an electric power company to direct current

10:02 JST, August 24, 2022

It’s been around 50 years since Kachidoki Bridge in Chuo Ward, Tokyo, was last raised to allow the passage of marine traffic, but it’s still technically one of the largest bascule bridges in the country. Spanning the Sumida River, the bridge connects the Tsukiji and Tsukishima districts near the river’s mouth.

Constructed in 1940, its two bascules rise along a 44-meter segment in the middle of the 246-meter bridge. It was the first double-leaf bascule bridge in the country, and during its peak use, the bascules were raised for 20 minutes seven times per day to facilitate maritime traffic. But as the bridge saw more and more vehicles traversing it, among other reasons, it has not been raised since 1970.

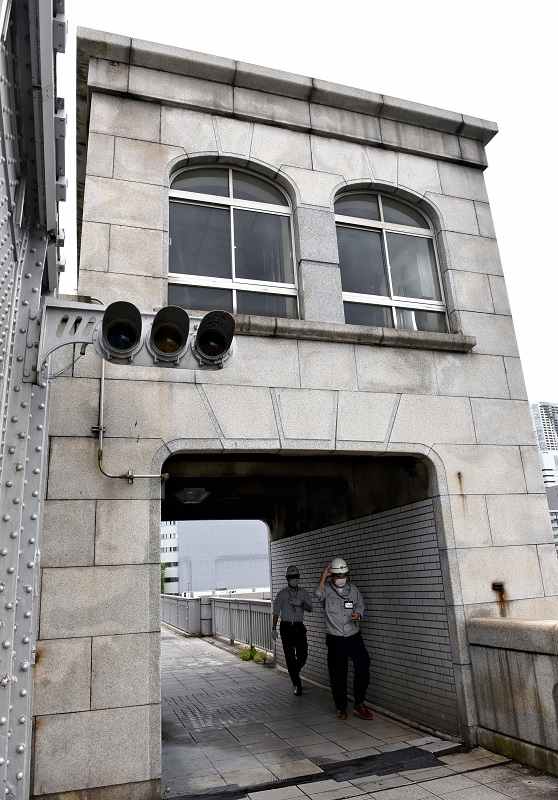

Kachidoki Bridge in Chuo Ward, Tokyo, is seen with traffic lights that were in use when the bridge was still raised and lowered.

A building near the foot of the bridge on the Tsukiji side was used as an electric power substation to help operate the bascules, but the once powerful equipment has rusted and the room housing it now has a feel of long-lost nostalgia.

The bridge’s columns were installed with four 125-horsepower electric motors and direct-current electricity enabled them to move the massive bridge segments through the control of their rotation speeds. The substation was constructed to convert alternating current provided by an electric power company into direct current.

A plate on the wall of the Kachidoki Museum of Bridges shows that the building was an electric power substation in the past.

After the raising of the bridge was permanently halted, the substation was used as a storage house. It was converted into a museum in 2005. Real equipment from the bridge is on display, as well as models of bridge parts and information about other bridges that span the Sumida River.

The Kachidoki Museum of Bridges is operated by the Tokyo Metropolitan Public Corporation for Road Improvement and Management.

When I stepped inside the museum, my eyes immediately zeroed in on two power generating systems. When in use, they would run alternately. But when additional power was needed to raise the bridge because of strong winds or other factors, they operated in tandem to send more electricity to the motors whirring inside the bridge’s columns.

The museum also features a 1:100 scale diorama showing how a ship passes under the bridge when raised. On the second floor, large switchboards fill the walls, and there are also design drawings of the bridge.

“I hope visitors will look at the wonderful technologies from that time,” said the museum’s director, Kenji Hosokawa, 71.

This structure housed an operating room for the bridge in the days when it was still raised and lowered.

After the bascules stopped opening and the substation shuttered, many people said they wanted to see the bridge in action again. But according to the Tokyo metropolitan government’s Bureau of Construction, it’s a difficult process.

“There are cost issues, and it would also be necessary to close the bridge [to traffic] for a long time to make it capable of opening and closing again,” an official of the bureau said. “So that would be difficult.”

I left the museum and looked at the bridge, picturing the double-leaf bascules rising once again.

Kachidoki Museum of Bridges

The museum opened in May 2005. Some of the exhibits are not related to the Kachidoki Bridge, such as panels introducing drawbridges across the country. The museum is an eight-minute walk from Kachidoki Station on the Toei Oedo Line and from Tsukiji Station on the Hibiya Line.

Address: 6-20-11 Tsukiji, Chuo Ward, Tokyo

Hours: 9:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. on Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays and Saturdays. Closed from Dec. 29 to Jan. 3.

Admission: Free