Five years on, shooting victims fight for government to admit liability

Flags fly outside the former First Baptist Church on June 7, 2022, in Sutherland Springs.

12:26 JST, August 17, 2022

SUTHERLAND SPRINGS, Texas – Ryland Ward knows he looks different from other kids, though it’s hard for him to talk about why.

When he moved to a new school in Lampasas, the small Central Texas town where he lives with his mother, the 10-year-old felt other children staring at him when he wore a T-shirt to class. Just below his sleeve, at the crook of his left elbow, a deep chunk of flesh is missing – as if a monster had taken a bite out of his arm.

That monster was a high-velocity bullet, and the cavernous scar a lifelong physical reminder of the gunshot wounds the boy sustained when a man armed with an AR-15-style rifle opened fire inside the First Baptist Church of Sutherland Springs in 2017.

Twenty-six people were killed and 20 others were wounded in the attack, including Ryland, who was shot at least four times at close range. The bullets exploded through his left arm, stomach, pelvis and left leg, causing such destruction to his 5-year-old body that doctors still can’t say for certain how many bullets hit him.

Like Ryland, many who were directly affected by the shooting continue to suffer physical and emotional pain years later. But their anguish has been exacerbated by a legal battle with the federal government over its failure to stop gunman Devin Kelley from purchasing his weapons – by forwarding information about his violent past that would have been caught in a background check. After survivors were forced to paint in excruciating detail the enduring toll of the massacre, a federal judge found the government liable.

Yet the Department of Justice gave notice in June it planned to appeal, although more recently it has opened the possibility of a settlement. Its grounds for an appeal are not yet known, but in the trial it argued that background checks would not have stopped the bloodshed – a position that clashes with the Biden administration’s strong support of background checks and tightened restrictions on access to weapons.

Dozens of Sutherland Springs victims, including Ryland’s mother, brought the suit against the United States Air Force in 2018 after the branch admitted it failed to report Kelley’s history of violence, including a 2012 conviction for domestic assault to the FBI. That conviction, which led to his dismissal from the Air Force, should have prevented the former airman from being able to buy the guns he used in the attack, which ended with Kelley’s suicide.

U.S. District Judge Xavier Rodriguez found the Air Force was 60% liable for the shooting, citing disturbing details uncovered in the case, including that Air Force officials were aware Kelley had previously researched and threatened a mass shooting and had a history of severe mental health issues that led officials to declare him to be “dangerous” and “a threat.”

According to testimony and evidence in the case, Air Force officials were so alarmed by the gunman’s threats of violence that he was permanently barred not only from the New Mexico air base where he served, but all bases around the country. Yet officials still failed to report his conviction to the FBI or warn others of his potential for violence, a decision that Rodriguez condemned in a July 2021 ruling, which dismissed the government’s argument that Kelley’s violence was “unforeseeable.”

In February, Rodriguez ordered the government to pay more than $230 million to 84 victims and survivors. But the government’s appeal has delayed any final outcome, leaving survivors struggling to pay expensive, ongoing medical bills and feeling betrayed by their own government.

Left : Ryland Ward shows a gunshot wound on his leg. After the shooting, doctors said Ryland had lost 80% of his blood. His heart stopped beating twice on the operating table.

Right : Ryland Ward shows a gunshot wound on his left arm on June 8, 2022.

***

Ryland doesn’t like to talk about what happened – not with his mother, with his doctors, much less other kids. He had tried to hide the scar on his arm and the others that line his small body so that maybe no one would notice. But the whispers at school felt like taunts. “Why does your arm look like that?” a classmate pressed him, as other kids stared.

One day, it became too much. “I was shot!” Ryland, who was 9 at the time, cried out in frustration. He lifted his shirt to show his classmates the jagged scar that runs down his chest toward his pelvis. “That’s what happened to me!” In tears, he was sent to the principal’s office and later went home.

Ryland’s mother, Chancie McMahan, knows her son is lucky, having survived horrific injuries from bullets designed for the battlefield. But what she hadn’t realized when Ryland was wounded, she said recently, was that the shooting “was only the beginning.”

Ryland’s pain has been more than physical. He has suffered nightmares since the shooting, after which he would wake up screaming. Lately his trauma has grown more intense, his emotions more on edge. A doctor told McMahan that her son was now old enough to understand what had happened to him and others inside the church. “His psychiatrist says the older he gets, the worse it’s going to get,” McMahan said.

McMahan wore a bittersweet smile as her son and his younger sister enjoyed a beat of normalcy, playing together at a park near their house and giggling in the light of a hot Texas afternoon. But McMahan was also anxious – about her son’s mounting medical bills and how she would be able to afford taking off work to care for him when upcoming surgeries force him back into a wheelchair.

“What people don’t understand is how something like this changes your life,” McMahan said. “There’s the shooting. . . . And then there’s what happens after.”

Records in the court case, including testimony from victims and the physicians who have treated them, document debilitating physical injuries, widespread depression and continued trauma that had led some to wish they had not survived the shooting. “Sometimes I wish I was dead,” one of the wounded told her doctor, according to court filings.

More than a dozen victims and family members, including McMahan, took the stand giving bleak testimony about the shooting and its aftermath. Rodriguez later outlined those agonizing accounts in his nearly 200-page judgment, transforming a usually mundane court order into a piercing document of how a mass shooting reverberates across generations.

A man who lost nine members of his family, including his parents, pregnant wife and three stepchildren, spoke about his flashbacks in which he sees his family murdered, how the faces of his wife and kids were “just a crater” after the gunman shot them. He recounted his stepdaughter, who was 7 at the time of the shooting and was injured but not shot, telling him how she heard her mother begging for the lives of her children and how the gunman responded by shooting them first.

Ryland had become known as the massacre’s “miracle child.” A volunteer firefighter had raced to the church minutes after the shooting. Inside the sanctuary, he had scanned the blood-soaked, disfigured victims strewn in piles across the floor looking for any signs of life. Then he felt a faint tug on his pant leg.

Looking down, he saw a tiny hand reaching out from beneath a stack of bodies. The boy’s left arm was barely hanging on. His torso and pelvis area had been blasted open. Blood was pouring from a large hole in his left leg. At the hospital in San Antonio to which he was rushed, doctors said Ryland had lost 80% of his blood. His heart stopped beating twice on the operating table. He spent weeks in a coma.

Lawyers for the victims called what their clients had been through “shocking, horrific and inhumane.” Rodriguez agreed, calling out the U.S. government for failing to stop the attack.

“The trial conclusively established that no other individual – not even Kelley’s own parents or partners – knew as much as the United States about the violence that Devin Kelley had threatened to commit and was capable of committing,” Rodriguez wrote.

But then came the government’s notice that it would appeal – filed just days after the shooting at an elementary school in Uvalde, Texas, another small town 115 miles west of Sutherland Springs.

In a statement, Dena Iverson, a DOJ spokeswoman, said the department had to give notice by June or give up its right to appeal. “The Department will continue to engage in a review of this case while it remains on appeal in the Fifth Circuit, considering all options for reaching a resolution, including possible mediation or settlement,” Iverson said. “By filing this notice, the government continues its close review of the legal issues presented.”

“The Department is dedicated to doing everything in its power to prevent senseless gun violence that continues to take countless innocent lives,” Iverson added.

The government’s decision to appeal the judge’s order led several involved in the case to accuse the Biden administration of hypocrisy – of trying to “avoid accountability” even as President Joe Biden and other administration officials have pressed for action in the aftermath of recent mass shootings.

At trial, government attorneys unsuccessfully argued, in part, that background checks would not have “deterred” Kelley from buying weapons because his “determination was such that he would utilize any means necessary to commit the mass shooting,” according to a May 2021 court brief signed by several Justice Department lawyers, including Brian Boynton, an assistant attorney general who leads the department’s civil division.

Government attorneys also said that Sutherland Springs survivors were asking for too much money. The government had proposed a settlement of just under $32 million for the 7 dozen victims – far less than what it had paid to settle other claims over mass shootings.

Last October, the Justice Department agreed to pay $88 million to the families of nine people killed in the 2015 shooting at Emanuel AME Church in Charleston, S.C., to settle claims that background check errors allowed the gunman to buy a weapon. Weeks later, the government agreed to pay $127.5 million to the families of those killed in the 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Fla., over claims the FBI failed to act on tips about the gunman.

On Aug. 5, the White House cited the shooting in Sutherland Springs as it touted the Biden administration’s efforts to “protect places of worship” – including funding for additional security measures and other efforts to reduce gun violence.

When Biden invited families of those who had been killed in mass shootings to the White House in July to watch him sign a bill aimed at curbing the scourge of violence, including a strengthening of the background check system, the Sutherland Springs victims were not included in the Rose Garden ceremony. The White House did not immediately respond when asked why.

Jamal Alsaffar, the lead attorney representing the Sutherland Springs families, highlighted the gulf between Biden’s policy favoring background checks and the Justice Department’s contention during the trial that an accurate check would not have dissuaded the gunman – an argument he expects to be repeated as part of any government appeal.

“Publicly giving lip service that background checks work, on the one hand, and then on the other filing a legal appeal that will likely require them to argue that background checks don’t work is a terrible look,” Alsaffar said. “Is the DOJ really going to undermine President Biden’s national gun policy by arguing that background checks don’t work?”

Attorneys for the victims have called it “unconscionable” that the suit, already marked by extensive delays, would be lengthened further by an appeal.

“We are talking about people who wake up every single day in pain. . . . We all pray that these people find peace and find a way to watch the sun rise every day,” said Bob Hilliard, a lawyer who represents McMahan.

***

As one of the plaintiffs, McMahan sued for nearly $30 million in damages to compensate for Ryland’s physical injuries, pain, trauma, future medical bills and likely loss of earnings in the anticipation that he will spend the rest of his life dealing with physical and mental health issues.

The Justice Department recommended less than $2.1 million for Ryland – a total that McMahan said she did not believe would cover her son’s needs.

Without any certainty in the case, McMahan has been a “ball of nerves” – worried about her son and the coming bills. The single mother, who works as a doctor’s assistant, had been given time off this summer to care for Ryland after his latest surgery – another procedure to deal with issues with his left leg and hip – but it was unpaid. To make ends meet, she set up a GoFundMe with the hashtag #RylandStrong.

McMahan recalled seeing her son for the first time after the shooting at the hospital, unconscious and hooked up to tubes and machines. She pulled back a blanket and found only clear tape holding his small body together, as doctors prepared for surgeries. “I dropped to my knees,” she recalled. “It was the worst thing I have ever seen. Something no one should have to see . . . I kept thinking, ‘How could someone do this to a child?'”

His dozens of surgeries since have left him in a wheelchair for long stretches. He will likely never be able to have children or walk normally, doctors have told McMahan. He has permanent nerve damage in his arm and buttocks. His body is still riddled with bullet fragments that are too dangerous to remove. Like other survivors, he faces many more operations.

As McMahan explained the extensive medical procedures to come, Ryland sat at her side, quietly listening. Moments earlier, he had been enthusiastically pressing his mother to let him go swimming. “Or fishing! Let’s go fishing!” he said. McMahan had told him to go play, but Ryland stayed put, a shadow falling across his face as he listened to her.

“Another surgery after this surgery?” he asked, his enthusiasm for a free summer afternoon suddenly vanishing. Dejected, he stood up and slowly walked away.

“I don’t care about money, but I care about my child and what he’s going to need for the remainder of his life,” McMahan said. “Because this is about the rest of his life. This isn’t going away. We’re going to have this surgery and then another one and then another one. . . . And it baffles me why the government won’t just take responsibility for their missteps, how they are trying to lowball people who are suffering and will suffer for the rest of their lives.”

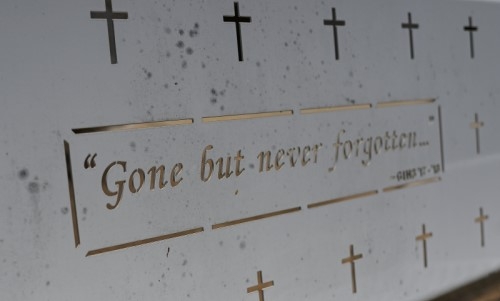

A bench with crosses sits outside the former First Baptist Church on June 7, 2022, in Sutherland Springs.