For U.S. troops who survived Kabul airport disaster, guilt and grief endure

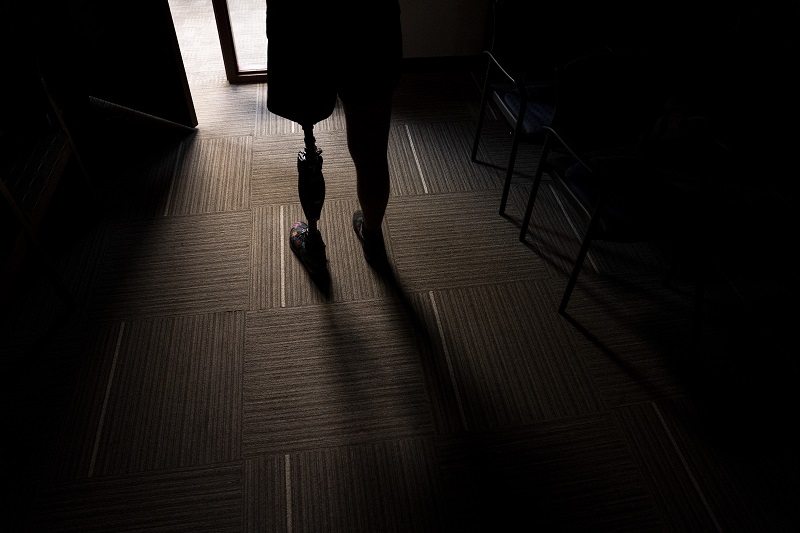

Marine Sgt. Tyler Vargas-Andrews, a double amputee, is seen at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Md., on Aug. 4.

14:00 JST, August 25, 2022

Marine Sgt. Tyler Vargas-Andrews at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center.

From a guard tower overlooking Kabul’s airport, two U.S. Marines spotted a man matching the description of a suspected suicide bomber. They radioed their commanders: “Do we have permission to engage?”

Request denied, one of the Marines, Sgt. Tyler Vargas-Andrews, recalled being told. Too many civilians nearby.

The man vanished from view among a crush of people clamoring outside the airport’s Abbey Gate, he said. It was Aug. 26, 2021. Hours later, an explosion ripped through the crowd, killing an estimated 170 Afghans along with 13 U.S. troops.

Vargas-Andrews contends that “unfortunately, a lot of people died” because he was directed to stand down. “That’s a hard thing to deal with,” he said. “You know, that’s something that, honestly, eats at me every single day.”

The 24-year-old, from Folsom, Calif., climbed down from the tower a short time before the explosion went off and suffered catastrophic wounds in the blast. He has undergone 43 surgeries since, losing his right arm, left leg, left kidney, and parts of his intestines and colon. At least 15 metal fragments remain embedded in his body, he said, silent reminders of the day he almost died.

It’s unclear if the bombing at Abbey Gate could have been averted. The event was a low point in the United States’ exit from Afghanistan and the treacherous operation that began when Taliban foot soldiers swept into the capital 11 days prior. For the American military personnel involved, much of their experience throughout those two weeks is still coming into focus now, a year later, as they process the suffering they witnessed, and cope with lasting feelings of anger, guilt and grief.

This account of the deployment and the attack, carried out by an Islamic State affiliate in Afghanistan, is based on interviews with 14 service members involved, including the top military commander who planned and directed the operation.

In blunt, often visceral detail, those who survived the final days of America’s longest war made clear that what endures is an incalculable sense of loss.

The commander, Marine Gen. Kenneth “Frank” McKenzie, said that he, too, continues to process what occurred, and regrets both the Abbey Gate bombing and a drone strike U.S. forces carried out three days later near the airport, killing 10 civilians. U.S. troops involved mistakenly believed they were targeting another suicide bomber, the Pentagon later concluded.

“We all feel bitterly what happened at the end,” the general said.

Heart-pounding and heartbreaking

Nearly 6,000 U.S. service members were dispatched to Afghanistan as Kabul fell, in what would be the greatest test of the Pentagon’s emergency-evacuation planning since the Vietnam War’s devastating conclusion decades earlier. Nearly 125,000 people were rescued over 17 days. But tens of thousands more were stranded, many with no clear path to be reunited with family in the United States.

For many of the troops rushed to Hamid Karzai International Airport – named for Afghanistan’s first leader after U.S. forces ousted the Taliban from power as vengeance for quartering the terrorist group responsible for 9/11 – it was their first taste of a war that, after nearly 20 years, already was lost.

The sudden crisis undercut President Joe Biden’s promise of a “safe and orderly” withdrawal, and prompted McKenzie to cut a deal with the Taliban in which coalition troops controlled Kabul’s airport while America’s longtime battlefield adversary pledged to maintain order outside.

U.S. personnel involved in the mission said the arrangement was exasperating, with militants beating and executing Afghans as they approached the airport. McKenzie described it as a strained but transactional relationship that provided U.S. troops with a measure of security from the Islamic State, which also is in conflict with the Taliban.

A Defense Department review of the operation, first detailed by The Washington Post in February, exposed sharp disagreements within the U.S. government over how to carry out the withdrawal. State Department officials wanted to keep the U.S. Embassy in Kabul open as long as possible, frustrating the military brass who wanted to begin the evacuation of American citizens and Afghan allies sooner.

Top commanders, including McKenzie, had advised Biden against withdrawing all U.S. forces from Afghanistan, preferring to keep a force of about 2,500 in place that would be reinforced by a similar number of coalition troops and backed by air power. But when the president announced in April 2021 that he wanted the military out by that September, the Pentagon began preparing for an evacuation.

A few hundred soldiers from the Army’s 10th Mountain Division were positioned at the airport in spring of 2021 to maintain security in Kabul. They were intended to be a safety net as the administration, leery of Taliban gains elsewhere, had hoped to retain a diplomatic presence after the military withdrawal was complete.

The Afghan government’s collapse on Aug. 15 triggered mass panic, leading tens of thousands of Afghans, many of them American allies who aided the war effort, to rush the airport. First Sgt. Andrew Kelly, of the 10th Mountain Division, said his unit tried but failed to prevent the chaos that unfolded as people, desperate to flee, swarmed the flight line and attempted to reach any aircraft they could find.

In the hysteria, Kelly and other U.S. soldiers responded to a report of gunshots at a traffic circle outside the airport’s commercial terminal. As civilians scrambled for cover, a firefight broke out when gunmen brandished weapons at the Americans. U.S. soldiers killed three of them and wounded a fourth.

The small contingent of U.S. troops, linked arm-in-arm at times, attempted to hold back the masses. But the determined civilians broke through, with some boarding parked C-17 cargo planes without permission, and others climbing onto the outside of aircraft before takeoff only to fall to their death moments later.

“That’s how desperate they were to get out of there,” said Army 1st Lt. Timothy Williams. “It was one of those defining moments, I think, for everybody where it was just like, ‘Wow, this is terrible.'”

As C-17s carrying American reinforcements touched down, Marines and soldiers were assigned to secure the airport’s gates, and to assess, search and admit evacuees. It was heart-pounding, often heartbreaking work.

Among the units instructed to reopen Abbey Gate was the 1st Platoon of Ghost Company, 2nd Battalion, 1st Marines. Comprising less than 45 troops, it had been in Jordan serving as part of a crisis-response force when commanders ordered their departure for Kabul. The group was tightknit and had been training for months, said Gunnery Sgt. Jonathan Eby, the platoon sergeant.

Eby, a 17-year Marine with previous experience in Iraq and Afghanistan, said they formed a line and surged toward the crowd trying to move people backward. There was a writhing, anxious energy, he said, likening the crowd to a mosh pit.

“I would compare it to whatever Leonidas and his Spartans felt like trying to hold back all those people,” Eby said, referring to the ancient Greek king and his warriors, who were vastly outnumbered in a famous battle depicted in the movie “300.”

In the ensuing days, the Marines maintained a barricade at the gate, adjacent to a fetid drainage canal along the facility’s southeastern edge. Many Afghans figured out that wading through the filth was the easiest way to bypass the crowd. Those flashing the requisite paperwork were hoisted to safety. U.S. troops carried out similar work at other entry points.

Teams of U.S. service women, formed on the fly in preparation for the evacuation, supplemented the mission by searching women and assisting children, hundreds of whom had reached the airport without any parent or guardian, or wound up separated along the way.

Marine Warrant Officer Sasha Savage at Camp Lejeune on July 18.

Warrant Officer Sasha Savage, who led a team of eight women, said the effort never truly found a rhythm, but they assisted who they could. Photographs of her teammates caring for babies went viral online. It was clear that the evacuees were “going through the hardest time of their life,” arriving dehydrated, bloody or scared because their families had been separated in the mayhem, she said.

“It feels like you’re making impact at that point,” Savage said.

To get around the airport, U.S. troops hot-wired baggage carts, forklifts and other vehicles. They pilfered tools found in shipping containers, figuring they might prove useful. Vargas-Andrews grabbed a pair of 18-inch bolt cutters.

At Abbey Gate, he and his scout-sniper teammates took turns scanning the crowd from the guard tower. Several times, he said, Marines interfacing with those hoping to flee retreated into the base of the tower to cry. The Taliban were posted at checkpoints just yards away, and watching them act so ruthlessly made it difficult to maintain restraint.

Vargas-Andrews recalled that after a few days of observing Taliban abuses, he crept closer to their checkpoints to photograph corpses nearby – people the militants had killed, he surmised. He relayed the images to commanders, he said, but understood there would be no recourse.

“If we start firing at them, they’re going to start firing at us. Do we want to get in that scenario?” he said. “I get it. But it’s a hard thing.”

A flash and then ‘Boom’

Fire from the explosion swallowed the tightly packed corridor outside Abbey Gate, ejecting ball bearings that cut down those closest to the epicenter and left a gruesome path of carnage. U.S. personnel manning the gate had been warned that a suicide bomber was likely to be nearby, but they had not received orders to suspend operations.

Asked about Vargas-Andrews’s contention that the bomber could have been killed before the explosion, McKenzie said that no request to do so reached his level or surfaced during a military investigation of the incident that included testimony from more than 100 U.S. personnel. Vargas-Andrews said he was never interviewed as part of that inquiry as he underwent numerous surgeries.

Eby, who also was at Abbey Gate when the bomb exploded, said that there was a “known threat” in the area, but he was unaware of any service member identifying the bomber. “All that was ever said was, ‘Look for a black bag,'” Eby said.

Shortly before the blast, Vargas-Andrews had climbed down from the tower to help people into the airport. He recalls seeing a flash. And then, “Boom – this massive wave of pressure just hit me,” he said.

“The next time I opened my eyes, I’m on the ground,” Vargas-Andrews recalled. To his left, a sea of people were down and lifeless.

The military investigation, released earlier this year, determined the loss of life from the bombing was from a single catastrophic explosion. Some dispute that, though. Multiple personnel posted at Abbey Gate said they heard gunfire as well – and that they shot back.

Vargas-Andrews and others with him at the time remain convinced the bombing was part of a complex attack. As he lay in the dirt, his arm and leg shredded, the sound of gunfire crackling overhead urged him to seek cover, he said. There was a hole in the fence line about 70 yards away, but his wounds made it impossible to drag himself there.

Investigators concluded that gunfire was sporadic, and that those believing otherwise may have been disorientated by the explosion.

Those unharmed – or not incapacitated – scrambled to save as many lives as possible.

Among them was Marine Sgt. Wyatt Wilson, who sustained grievous shrapnel wounds in the blast and was thrown off his feet by its force. Despite his injuries, he tried to drag another severely wounded Marine to safety, but he had lost too much blood. The woman Wilson tried to help, Cpl. Kelsee Lainhart, was left paralyzed by the explosion.

Teammates of Vargas-Andrews knew he was in trouble after the blast. Sgt. Charles Schilling, a close friend, raced to him, screaming Vargas-Andrews’s name repeatedly. Using the bolt cutters his friend had commandeered, Schilling ripped open a hole in the fence to shorten the distance they’d need to traverse for medical care. The injured were whisked away on any vehicle available.

“Patients kept coming in five, six at a time,” said Capt. Carlos Mendoza, an Air Force flight nurse who was working at the airport’s hospital a few miles from the blast site. “It just didn’t stop.”

The wounded were splayed out on the floor waiting for care as doctors triaged them. Mendoza recalled encountering one service member who had died and another who was mortally wounded. Chaplains arrived and administered last rites.

A doctor split open the chest of one Marine using a pair of scissors as they searched for interior bleeding and then rushed him to surgery, Mendoza said.

“I heard that he survived,” he added, though he is unsure.

Thirty-seven Marines were awarded Purple Hearts for injuries sustained in the attack, said Maj. Jordan Cochran, a spokesman. More than 300 received ribbons stipulating that they engaged in direct combat over the course of the evacuation.

In the Army, at least four soldiers have received Purple Hearts for injuries suffered in the evacuation, said Maj. Jackie Wren, a service spokeswoman. Nearly 330 soldiers were recognized for experiencing combat during those weeks.

About 45 U.S. troops were wounded in the bombing and survived, the Pentagon said.

- he Americans killed:

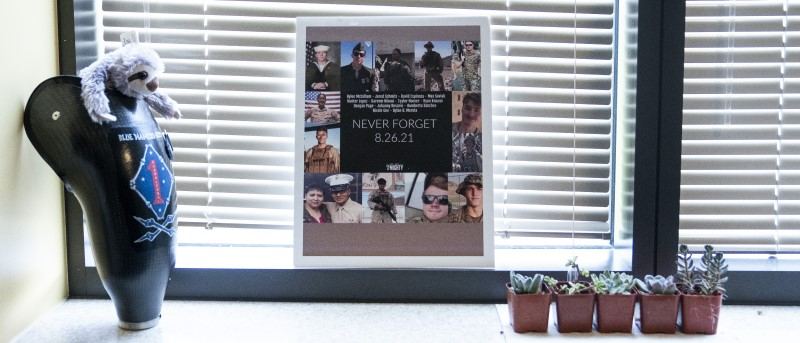

- Marine Lance Cpl. David Espinoza, 20.

- Marine Sgt. Nicole Gee, 23.

- Marine Staff Sgt. Darin Taylor Hoover, 31.

- Army Staff Sgt. Ryan Knauss, 23.

- Marine Cpl. Hunter Lopez, 22.

- Marine Lance Cpl. Dylan Merola, 20.

- Marine Lance Cpl. Rylee McCollum, 20.

- Marine Lance Cpl. Kareem Nikoui, 20.

- Marine Cpl. Daegan Page, 23.

- Marine Sgt. Johanny Rosario Pichardo, 25.

- Marine Cpl. Humberto Sanchez, 22.

- Marine Lance Cpl. Jared Schmitz, 20.

- Navy Hospitalman Maxton Soviak, 22.

The recovery

McKenzie, the commanding general, retired in April. He marvels at the courage and professionalism rank-and-file troops showed during the evacuation, and said his greatest fear was a bomber sneaking onto a plane and detonating in the air, killing hundreds of people.

Service members reflecting on the operation should “decouple their actions and their enormous courage on the ground” from decisions made by more senior U.S. officials that put them there, he said.

“If you’re going to bring people in, you have to search them,” he said. “You’ve got to be confident that you’re not going to let someone with an explosive device get on an airplane because that is the point of greatest vulnerability.”

Eby, the platoon sergeant, lost nine men in his unit, all 23 or younger. During an interview last month at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, he paused several times to regain composure while recounting stories about the fallen. He considers the surviving members of the platoon to be family.

“We are inseparable,” he said. “I still get called ‘Dad’ by most of them.”

Savage, who led a female search team, wears a black metal bracelet engraved with Gee’s name. The weightlifting enthusiast had been meritoriously promoted, and was among the Marines pictured caring for Afghan children.

“She had a certain light and happiness about her that would make things positive no matter the situation,” Savage said.

Vargas-Andrews said he hopes the military enhances its recognition of those who saved his life and the lives of others. He singled out Schilling, who tore open the fence, and Hospitalman 3rd Class Jorge Mayo, who raced among the blast victims and treated Vargas-Andrews.

A memory from a few days before the explosion sticks with the Marine, as he continues physical therapy at Walter Reed National Military Medical outside Washington. In the crowd at Abbey Gate, he spotted a sobbing girl in tattered clothes, maybe 8 years old. She held an infant in one arm and the hand of a boy about 4 in her other hand. The baby wasn’t breathing.

Vargas-Andrews said he hustled the infant, who was turning blue, to an Air Force medic, and they resuscitated the baby. But the girl continued to cry.

He scrambled to a higher perch on top of a vehicle, and spotted a man with his head in his hands. It was the children’s father. The man had paperwork needed to evacuate but had been separated from his children in the melee. Their family was reunited moments later.

Vargas-Andrews said the moment was “huge for me,” his voice thickening with emotion as he recalled it.

“I look at my injuries every day,” he said. “And that one family, they have a life now. And that’s something that won’t be taken away from them.”

He shifted his weight in his chair, a prosthetic leg beneath him.

“You know,” he said, “there were a lot of moments like that out there, and it makes it worth it. It makes all this worth it.”

Marine Sgt. Tyler Vargas-Andrews put together a memorial inside his apartment at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center to honor the members of his unit who were lost in Afghanistan.