In Uvalde, murals connect artists and victims’ families

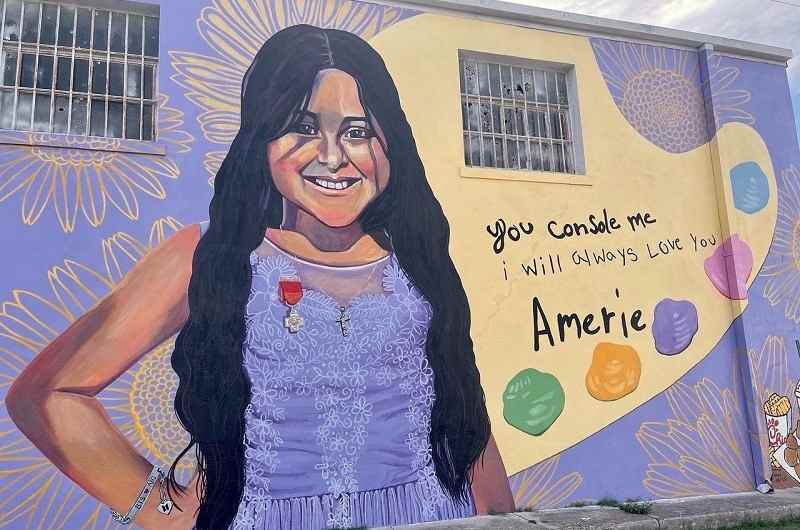

A mural of 10-year-old Amerie Jo Garza in Uvalde, Texas, painted by artist Cristina Noriega.

14:27 JST, September 7, 2022

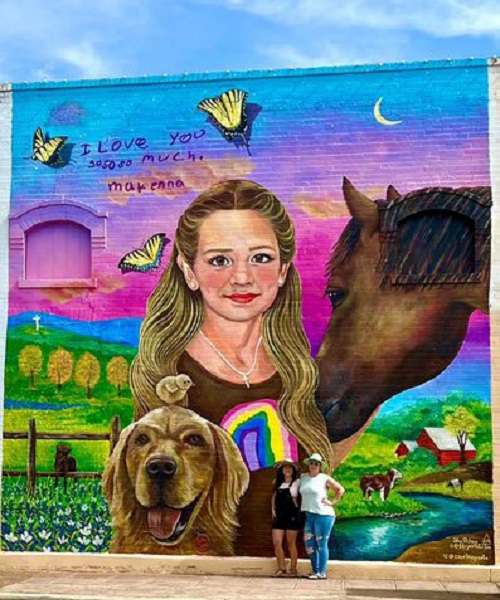

Artist Silvy Ochoa and her assignment partner pose in front of a mural in Uvalde, Texas, honoring 10-year-old Makenna Lee Elrod, who was among the 21 people killed by a gunman at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde in May.

For days, Silvy Ochoa stood atop an electric scissors lift as she stroked her paintbrush against a brick wall.

The artist had a difficult task: to re-create 10-year-old Makenna Lee Elrod’s portrait on a Uvalde, Tex., street using a picture chosen by the girl’s family and to tell the story of her life as told by her loved ones.

Makenna was among the 21 people killed by a gunman at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde in May.

Every detailed mattered, Ochoa told The Washington Post. Her hazel eyes must be the exact shade – one that hardly any camera could capture right – her mother told Ochoa. The golden retriever, her chicken, her horse and the rest of the animals that lived with the girl in her family’s ranch must be included. The handwriting of a note the girl had left her mother must be accurately reproduced.

On Tuesday, those who lived through the shooting returned to a different building for a new academic year.

But those who did not survive the May 24 rampage still live on the town’s walls. Makenna’s portrait is one of 21 murals – each representing the 19 children and two teachers killed – that 50 Texas artists painted during the course of three months.

“You don’t get over something like this,” said Cristina Noriega, the artist who painted 10-year-old Amerie Jo Garza’s mural. “But perhaps honoring who they were in these portraits – they’re everywhere in Uvalde now – brings some comfort.”

Artist Abel Ortiz n front of a mural in Uvalde, Texas, honoring 9-year-old Ellie Garcia, who was among the 21 people killed by a gunman at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde in May.

The idea was born a day after the tragedy, when Abel Ortiz, the artist who organized the project, was watching the news and kept asking himself what was the best way he could help the town heal from a shooting at the school his own children once attended.

All of the lead artists and their assistants donated their time, said Ortiz, who also painted a mural. The wall space was also donated. Paint and supplies were covered by donations and funds raised in an art auction.

“The only thing in my power was art, and art heals,” Ortiz told The Post.

So Ortiz got to work and in the next weeks he secured 21 walls, including one outside his art gallery, where he painted 9-year-old Ellie Garcia.

But before any painting could start, the victims’ families, who Ortiz said were not to be contacted until the last funeral, had to give their consent. Once every victim was formally mourned, Monica Maldonado, the founder of MAS Cultura, a nonprofit based in Austin and the project manager, reached out to the families to get to know the victims before pairing them up with an artist.

Once she had more details about the victim, Maldonado sent artists a form the families had filled out with information including the victim’s favorite color, food and activity, an unforgettable memory, etc. Based on this information, she paired the families with those artists who had some sort of connection to the victim, whether it was their personality, a hobby, an occupation or a life experience, Maldonado told The Post.

That’s how Ochoa was selected to paint Makenna’s mural. “I was a happy little girl like MaKenna,” Ochoa told The Post. “We both love nature. She hugged trees. I hug trees too!” Makenna was known for leaving hidden notes for those she loved; Ochoa does the same.

Once Maldonado reached out to Ochoa to pair her with Makenna, the artist started sketching the mural’s design. Her portrait would be the focal point of the canvas. Because Makenna lived in a ranch with her family, Ochoa wanted to create a more traditional design, she told The Post.

“Every single element has a meaning that connects her to her family and tells her story,” Ochoa said. “I didn’t want to make a collage but to tell her story.”

The four trees on the left of the mural represent Makenna and her three siblings – the ones with pink flowers for the three girls, and the one without for her brother.

The bluebonnets under the trees were the girl’s favorite flowers. The river with rocks with small specks of paint to the right of the girl represents one of her favorite hobbies, painting rocks. Eastern tiger swallowtail butterflies fly on top of her portrait.

Following Makenna’s death, an eastern tiger swallowtail butterfly attempted to sneak into her father’s car for about 10 minutes, her father shared with Ochoa, who selected this type of butterfly as a symbol that Makenna is still here. Before her father shared this anecdote, the butterflies were purple – her favorite color. The rainbow on Makenna’s shirt was painted by her family, Ochoa said.

The day Ochoa finished painting the eyes, Makenna’s mother came to see how the mural was unfolding. Her first reaction was to cover her mouth with both hands. Then she began crying.

It wasn’t until Ochoa was close to finishing the mural, which can be seen from the main streets, that Makenna’s mother realized she will see the mural almost every day. It stands on her route to work.

On her way to work, her daughter’s face can be seen on the reflection of the stores across from the mural. On the way back, Ochoa said, Makenna’s hazel eyes stare straight into her mother’s.