Donald Keene and Japanese POW Kept Warm Exchanges during Pacific War and Even after World War II, Letters Recently Found Show

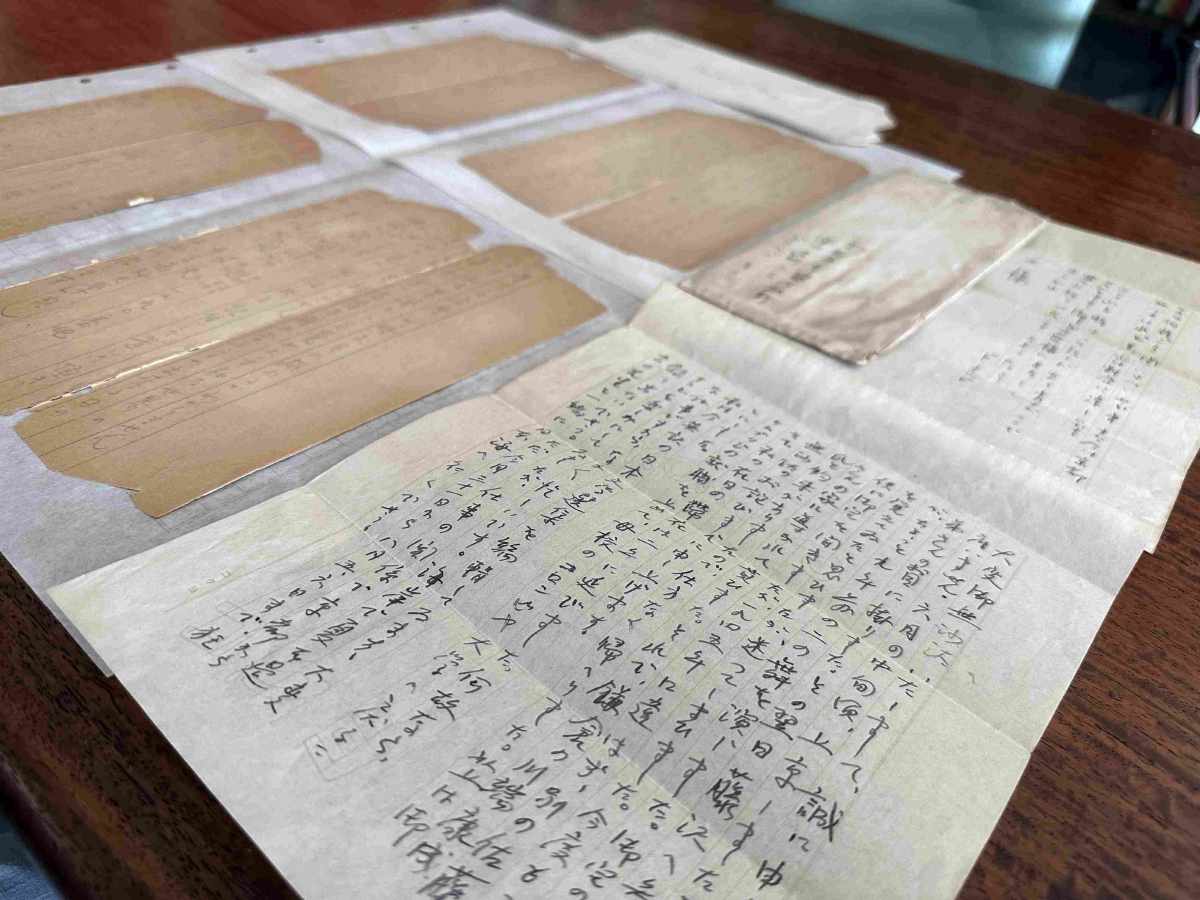

Donald Keene’s letter in Japanese to Takeo Sato in 1954, front, and Sato’s letter to Keene in 1944, while being held as a POW in Hawaii.

13:28 JST, July 30, 2024

Donald Keene, who helped spread the charms of Japanese literature around the world and died in 2019 at the age of 96, kept a warm exchange throughout World War II and in the postwar years with a Japanese prisoner of war he had interrogated in Hawaii during the Pacific War.

Keene’s adopted son, Seiki, 73, found a letter from the POW addressed to Keene in a bundle of letters his father left behind.

This summer, Seiki sought out and contacted the bereaved family, who coincidentally had also just found a letter from Keene to their father.

Seventy-eight years after the end of the war, a picture has emerged of Keene and the former POW deepening their friendship and respecting each other as human beings.

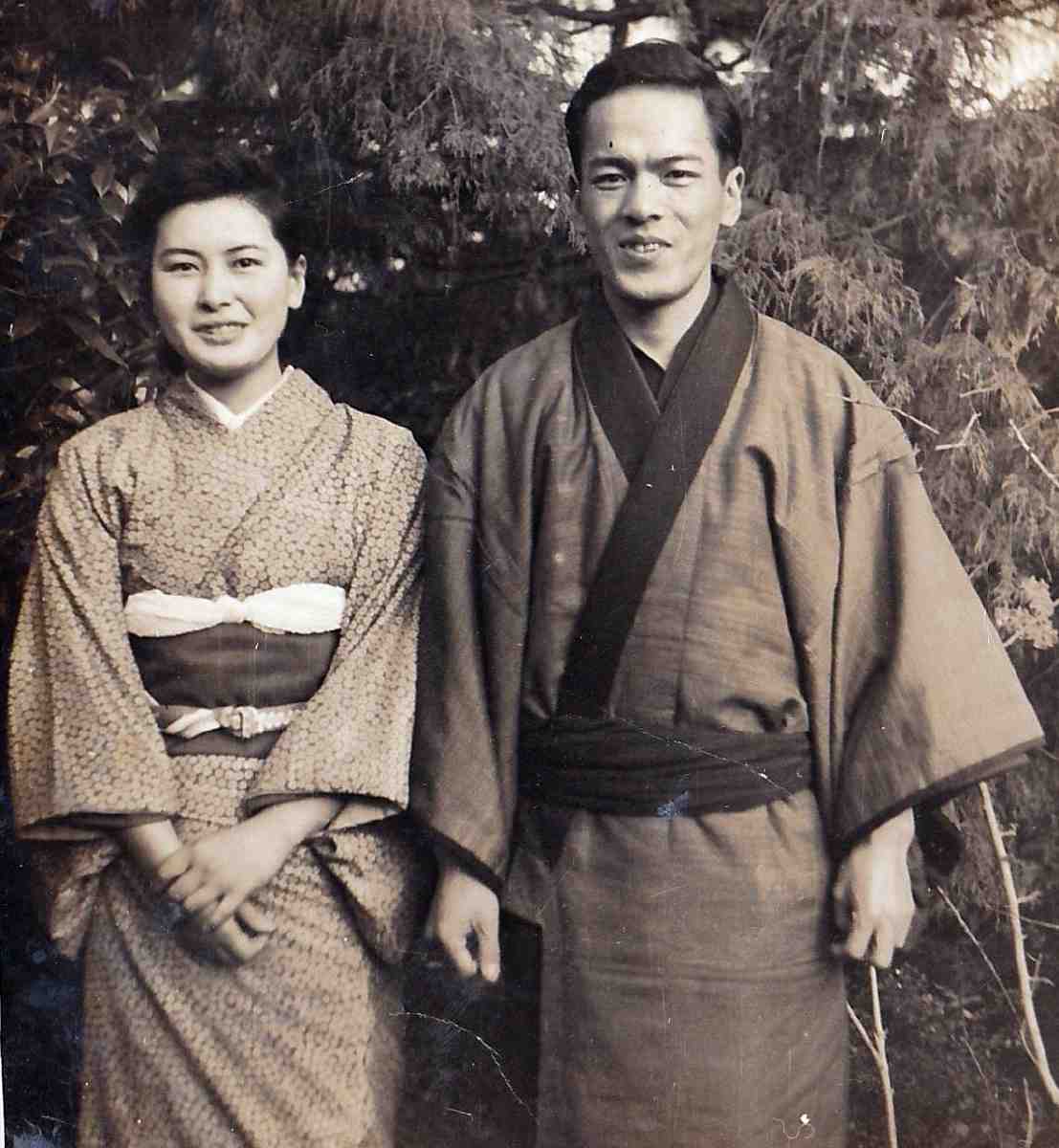

The former POW was Takeo Sato, who died in 2007 at the age of 88. After graduating from Tokyo University of Commerce (now Hitotsubashi University), he entered the Naval Accounting School. Sato served at bases including Kure naval headquarters in Hiroshima Prefecture before being assigned to Saipan in 1944.

Takeo Sato and his wife, Kishiko, are seen in the 1940s.

He was captured during the Battle of Saipan that lasted from June to July 1944 and sent to a U.S. military prison camp in Hawaii. One of the U.S. Navy Japanese language officers who interrogated him was Keene.

Sato’s letter found by Seiki begins with the words “Dear brother Keene” and was written on two sheets of paper in October 1944, while he was still a POW in Hawaii. He expresses his gratitude for meeting Keene, describes his life as a POW, and expresses his feelings with two tanka poems he composed.

At the end of the letter, he writes the following along with his home address in Japan:

“I don’t know when I will see you again. But I have no doubt that somewhere in the peaceful world where we have woken up from our nightmare, we will have a better chance to warm up our friendship.”

Keene’s letter discovered by the Sato family was dated nearly 10 years later, on July 29, 1954, and mailed to Sato’s home in Fujisawa, Kanagawa Prefecture. Keene had come to Japan the year before to study at the graduate school of Kyoto University.

The letter, written in Japanese on two sheets of paper, apologizes that when he came to Tokyo in June, he tried to visit Sato’s house but got lost and could not make it as he was about to meet Yasunari Kawabata, a great writer of the era, in Kamakura, not far from Fujisawa.

He then gave an update on his recent activities and concluded as follows:

“I am wondering when you will be in Kansai …We have many things to talk about when we meet.”

Donald Keene wears his U.S. Navy uniform around January or February 1942.

The two did meet in person after that.

Sato’s eldest son, Fumito, now 71, clearly remembers one thing about Keene: “When I was five or six years old, Keene-san gave me a small Japanese doll.”

Seiki said, “My father’s job in Hawaii was translation, but it seems that his best friend and boss arranged for him to interrogate POWs who seemed to be on the same page as my father.”

According to Keene’s autobiography and the chronology of the Donald Keene Memorial Foundation in Tokyo, he listened to Beethoven’s Symphony No. 3 “Eroica” in the shower room with the Japanese POWs, which Sato cited as his favorite piece of music during interrogation.

Since childhood, Sato had been familiar with literature, music, painting, and tanka poetry.

“Even though it was an interrogation, it seemed that they had a lot of fun talking about literature and music,” Seiki said, recalling a conversation he had with his father before his death.

Fumito was sorting through his father’s belongings at the family home in July this year when he happened to find Keene’s letter tucked into a book. About a week later, Seiki contacted him.

Fumito and his younger brother, Gento, 65, visited Seiki in July and donated Keene’s letter to the Donald Keene Memorial Foundation.

Sato rarely talked about the Pacific War to his sons, but there is still war going on in the world.

“I found that they respected each other and treated each other as human beings, regardless of whether they were POWs or officers, the defeated or the victorious,” Gento said. “I think that is very important.”

Fumito Sato, left, and his brother Gento, right, visit the Donald Keene Memorial Foundation in Kita Ward, Tokyo, in July this year. At center is Seiki Keene holding a portrait of Donald Keene.