New book highlights disabled people’s experiences in World War II

Chisako Sugiyama, who appealed for compensation for civilians injured during World War II

8:00 JST, August 21, 2022

Every year, the summer months see many articles and documentaries about World War II, but one subject that has rarely been addressed is what the war was like for disabled people. In what ways were they involved, and what was postwar life like for civilians who became disabled as a result of the conflict?

Documentary filmmaker Masayuki Hayashi compiled a book this summer titled “The Pacific War for Disabled People,” published by Fubaisha. I interviewed Hayashi about it this month, 77 years after the end of the war.

“At the time, blind people were thought to have better hearing than sighted people, so visually impaired people were assigned to be air-raid monitors in Ishikawa Prefecture,” said Hayashi, 68. “I wanted to confirm not only those facts, but also how effective those people were as air-raid monitors.”

Hayashi and I have been good friends for 16 years. I also interviewed him in the summer of 2006, when I was a reporter for the Yomiuri Shimbun, for a series of articles on the 61st anniversary of the war’s end. Hayashi produced films and TV programs on the theme of “war and people,” and he had just completed a film focusing on a civilian air raid victim.

His passion for uncovering facts has not waned — Hayashi’s latest book devotes different chapters to types of disabilities: visual, hearing, physical and mental. Drawing on more than 20 years of interviews and numerous documents, he meticulously lays out the historical background and facts, and examines the situation of disabled people during the war.

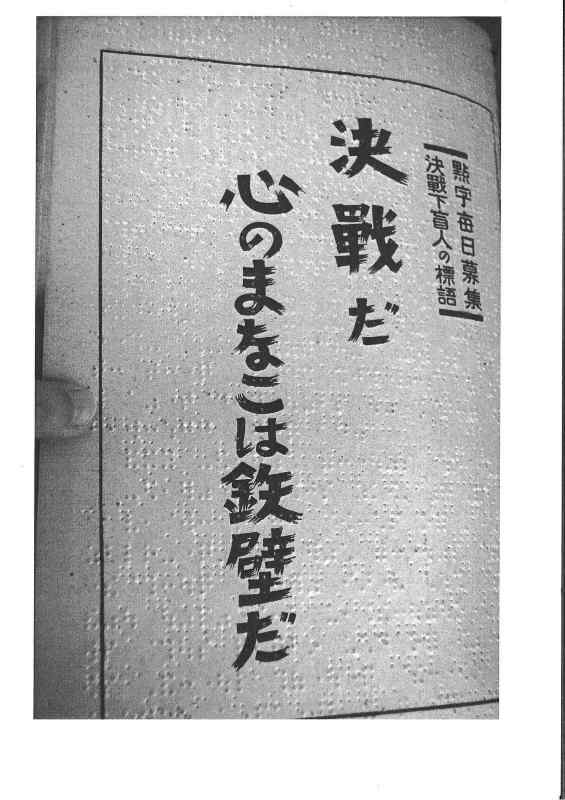

This slogan to inspire disabled people during the war reads: “This is the decisive battle. The eyes of the heart are made of steel.”

The Ishikawa Prefectural Museum of History, for example, has a record titled “Enemy Plane Bombing Sound Collection” that contains the sound of the engines of U.S. fighter planes and heavy bombers at altitudes of 1,000, 3,000, and 5,000 meters.

After the recordings were made in 1943, the Japanese military tested visually impaired people to see if they could distinguish the direction and types of U.S. warplanes. The results are unknown, but a visually impaired man who underwent the training in Tokyo is quoted in Hayashi’s book as saying: “I thought it would be useless.”

According to the book, there were visually impaired people who served as “hearing soldiers” in Germany, but such soldiers were never recruited in Japan.

However, in 1942, prior to the production of the record, Ishikawa Prefecture recruited 30 visually impaired people as air-raid monitors. They were assigned to monitor enemy aircraft attacks at night on the roof of a local police station, although no U.S. military aircraft ultimately flew overhead.

Hayashi said, “Disabled people actively sought to contribute to the mobilization of the disabled for the war,” an assertion he backs up in his book with interviews and documents.

For example, in 1942, the principal of the Gifu School for the Blind submitted a petition to then Prime Minister Hideki Tojo. “If 100,000 blind people throughout Japan were given the honor of working in the national defense sector through the wise decision of His Excellency, it would truly be a great blessing,” the petition said.

“The intention was to improve their status by helping the war effort,” Hayashi said. “There were many wounded soldiers who had lost their sight due to the war, and their reintegration into society and vocational training was actively supported by those who were born disabled.”

‘Born with poor vision’

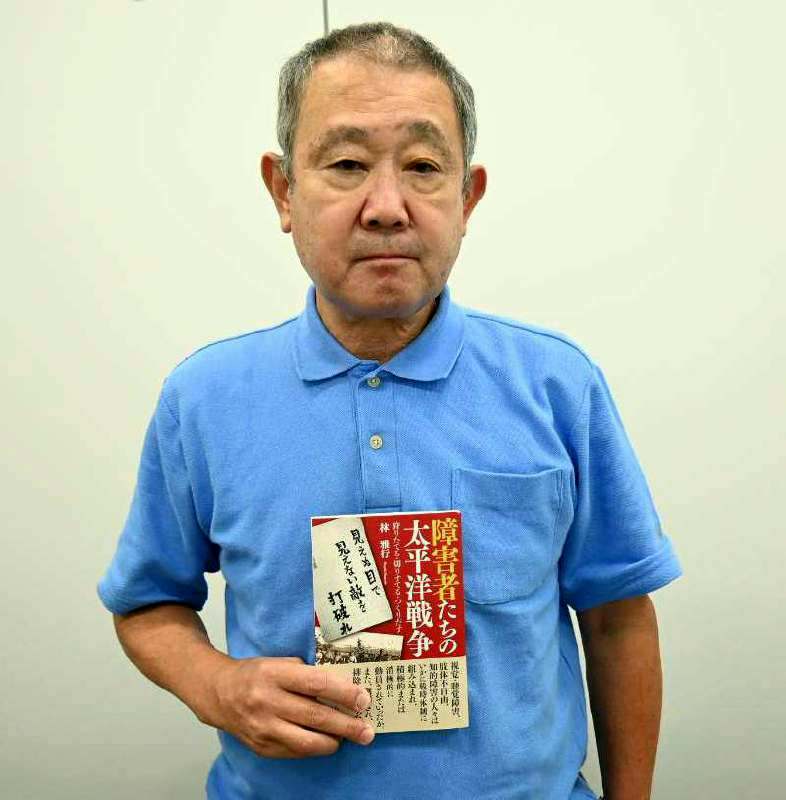

Masayuki Hayashi holds his book “The Pacific War for Disabled People.”

One of Hayashi’s main reasons for compiling this book was that he was born with amblyopia, giving him very little sight in his right eye.

His elementary school classmates teased him by calling him “Twenty-three Eyes,” an allusion to Sakae Tsuboi’s famous novel “Twenty-four Eyes.” He asked his parents, “Why did you have a child like me?”

Even as he grew up, Hayashi’s eyesight was a source of pain for him. He recently found an elementary school report card in which his right eye was written as “blind,” which brought back the bad feelings he had at the time.

In addition, Hayashi’s nephew is severely mentally handicapped and receives care at a facility on Izu Oshima island in Tokyo.

His recent book also details the little-known story of Fujikura Gakuen, a facility for the mentally handicapped on Izu Oshima island, and Seisen-Ryo, located on the Kiyosato Plateau in Yamanashi Prefecture at the southeastern foot of the Yatsugatake Mountains.

Fujikura Gakuen’s facilities were taken over by the Japanese military during the war, so children and other mentally handicapped people who had lived there traveled by train to Seisen-Ryo, which was a summer camp facility for the American football team of Rikkyo University in Tokyo.

Fujikura Gakuen in the 1940s

Today, Kiyosato has the atmosphere of a summer resort, but at that time, Seisen-Ryo was in the middle of what could be called a wasteland.

Ten lives were lost due to the harsh winter cold and hunger. Hayashi’s book includes a heartbreaking description of the mentally handicapped children pretending to eat as a form of play. They were remembering Izu Oshima island, where there was plenty of vegetables, fruits and other food.

Civilian activist

The latter half of the book follows the life of Chisako Sugiyama, who lost her left eye in an air raid in Nagoya. Sugiyama continued to appeal for state compensation for civilians disabled by air raids until her death in 2016 at the age of 101. When I first interviewed Hayashi, he had just completed the film “Hito no Ishibumi” (Monument to Humankind) about Sugiyama’s life.

In March 1945, a group of B-29 U.S. bombers flew over Nagoya, raining incendiary bombs on the city. Sugiyama’s house collapsed on top of her and she suffered a severe injury to her left eye.

After the war, she was outraged by the lack of compensation for civilians injured in air raids and founded the National Association of War Injured Victims in 1972. She continued to campaign with the “war injured,” including people who had lost their eyesight, been deafened by the sound of bombs, or lost limbs.

However, Sugiyama’s wish was never fulfilled. Compensation has been paid to A-bomb survivors, but not to ordinary war victims.

Chisako Sugiyama, left, visits war victim Hisae Kitamura.

Hayashi began recording footage of Sugiyama in 1999, or 27 years after the association was formed. Sugiyama was already 83 years old, but she was in high spirits. After that, they kept in touch both publicly and privately.

Sugiyama, who had had her left eye removed and had minimal vision in her right, said, “My eye is getting tired these days, but … I can still read the newspaper with a magnifying glass.” Hayashi was struck by her positive attitude and felt ashamed of his own complex.

“After that, I felt much closer to Sugiyama-san,” he said.

Russia has invaded Ukraine, and wars continue in the world, 77 years after the end of World War II. More people will become disabled due to the madness of war.

Hayashi said: “There are still many things I want to write about. I want to continue to convey the horrors of war.”