CCP on shaky ground ahead of party congress / China’s zero-COVID policy puts economy on shaky ground

Test tubes are lined up in front of a staff at a PCR testing site in Huludao, Liaoning Province in China.

20:00 JST, September 8, 2022

The Chinese government is facing a number of challenges as it prepares for the Communist Party Congress next month. This is first in a three-part series analyzing the issues.

***

In northeastern China in late July, an official in a protective suit took specimens from people’s throats using thin swabs and placed them into a series of test tubes 3 centimeters in diameter.

The sample collection was being conducted in a PCR laboratory in the suburbs of the city of Huludao, Liaoning Province. Each tube held 20 specimens to perform testing using pooled samples.

Under China’s zero-COVID policy, where not even the slightest infection with the novel coronavirus is allowed, it is not unusual in large cities that large-scale tests are conducted on as many as 10 million people in order to identify anyone who is infected.

The pooling method is common in China, allowing a large number of tests to be performed in a short time and with high efficiency, according to Chinese media.

Japan uses this method only for an exceptional cases, with the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry not in favor of using pooled samples. “Accuracy is just barely acceptable even with five specimens,” according to the ministry.

The Chinese government, however, raised the maximum number of specimens for each pooled test from five to 10 two years ago, and to 20 in January this year.

Beijing’s move apparently comes from its desire to reduce the cost of testing as much as possible, as well as to efficiently conduct tests.

A Chinese research institute estimated that inspections once every two days for a year for 500 million people in urban areas would cost 1.7 trillion yuan (about ¥34 trillion). China’s military budget this year was about 1.5 trillion yuan.

The Chinese Communist Party this spring announced a policy of having local governments, in principle, bear the cost of inspections. Consequently, a number of local governments have responded by passing the burden on to residents by charging for tests, or extending the validity period of the proof of a negative coronavirus test in an attempt to reduce the number of tests.

At the end of June, Chinese President Xi Jinping said the country would continue to adhere to the zero-COVID policy, saying that

China’s COVID-19 response measures are “the most economical and effective.”

Yet the unexpectedly prolonged infection situation is pushing vital local finances closer to the breaking point.

Xi is expected to secure an unprecedented third term as leader of the CCP at the party’s congress to be held this autumn. The recent sharp slowdown in the economy is a source of concern for Xi and the dominant position he has established within the party.

Reversal of fortune

The finances of Huludao, population 2.4 million, are in dire straits. Revenue in 2021 decreased 6.5% from the previous year to 9.6 billion yuan, while expenditures increased by 15% to 26.9 billion yuan, increasing its budget deficit by 30%. Expenses related to the novel coronavirus are the main reason for the increase in expenditures.

This year, the city is also expecting to be burdened with the huge costs of PCR testing. The city government is now charging several yuan for each effectively mandatory PCR test.

“In the end, the bill for the recession is passed on to residents,” said a 60-year-old unemployed man. “I’m really fed up.”

Revenue also shows no signs of increasing due to the real estate recession exacerbated by the pandemic.

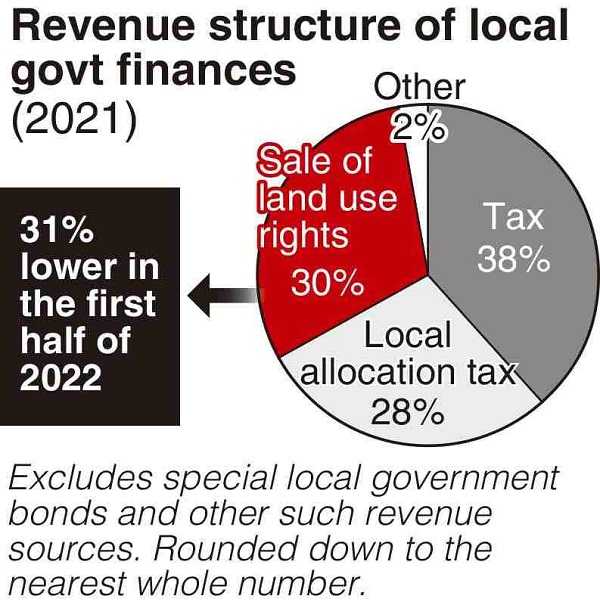

In China, where land is owned by the state in principle, land use rights fees paid by developers building condominiums have been a valuable source of revenue for local governments, accounting for an average of 30% of local revenues nationwide in 2021.

The Chinese-style growth cycle in which the real estate market enriches local finances and public works projects further stimulate the economy began to reverse into negative territory with the spread of the virus, causing local coffers to fall into perilous situations.

‘Danger zone’

Of China’s 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions, only Shanghai has a budget surplus. The municipalitiy’s gross domestic product, however, plunged 13% in the April-June period, hit hard by the lockdown of the city from the end of March to the end of May under the zero-COVID policy. In July, Beijing overtook Shanghai as “China’s largest economic city.”

The Yangtze River Delta region, which groups Shanghai and three neighboring provinces, is home to a large concentration of auto and other industries backed by foreign capital and accounts for 24% of the country’s GDP. The lockdown in Shanghai sharply slowed the country’s April-June growth rate to 0.4%.

“We apologize for the considerable inconvenience we have caused,” a senior Shanghai city official told a Japanese official at a meeting immediately after the lockdown ended. “We were not good enough, and this will not happen again.”

This was an unusual apology, given that zero-COVID is one of the Xi administration’s signature policies.

In a survey conducted in late April by the European Union Chamber of Commerce in China, 23% of member companies said they were considering either withdrawing or reviewing their investments. The survey result showed that the companies apparently did not like the authorities’ heavy-handed restrictions on their operations and employees’ behavior in the midst of the Shanghai lockdown.

According to a source close to the Japanese Embassy in Beijing, a U.S. company is offering a 50% increase in benefits to those posted to China, meaning that China is treated as a “danger zone,” the same as, for example, the African country of Angola.

Shanghai has held more than 20 briefings mainly for Japanese, European and U.S. local affiliates since June about how they would be able to ensure business continuity.

“It was like they made the rounds of their customers,” said a Japanese firm’s executive who attended a briefing. “They must be worried about us withdrawing from the market.”

The flight of foreign investment would undermine the growth of China’s local economy. Such withdrawal could further damage the real estate market, which accounts for just under 30% of China’s GDP when related industries are included.

Homebuyers stewing

The condominium complex under construction in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province in China

“I just want to move into the apartment that I bought and live there with peace of mind,” said Cao Yingying, a 42-year-old restaurant worker in Xi’an, Shaanxi Province.

She bought a unit on the 13th floor of an apartment building for 600,000 yuan 10 years ago in this ancient city in central China. But the apartment building is still under construction, though she has been continuing to pay the mortgage of 2,500 yuan per month.

More than 300 households frustrated by the situation began to live in the apartment complex without electricity, gas or water.

It is common in China’s real estate industry to sell pre-completed properties at a discounted price and use the money to fund construction. The pandemic has caused a string of construction stoppages across the country as builders’ cash flow deteriorates. Nationwide at nearly 300 properties, homebuyers in similar situations have started refusing to pay their loans.

It is estimated that 1.4% of all mortgages outstanding, totaling more than 500 billion yuan, will become nonperforming loans.

The anxiety and vexation of condominium buyers is turning into anger toward the government. More than 1,000 people including Cao’s husband participated in a protest in front of the provincial government building in the middle of July.

In late July, Reuters reported, “China will launch a real estate fund to help property developers resolve a crippling debt crisis, aiming for a warchest of up to 300 billion yuan in a bid to restore confidence in the industry.”

One of those developers, China Evergrande Group, is in a financial crisis that on its own has debts of 2 trillion yuan. This has also cast a shadow on failing finances.

The Xi administration is beginning to get bogged down by the side effects of its zero-COVID policy.