Kishida’s first-year report card / Kishida emphasizes ‘wage increase’ instead of ‘distribution’ in new forms of capitalism

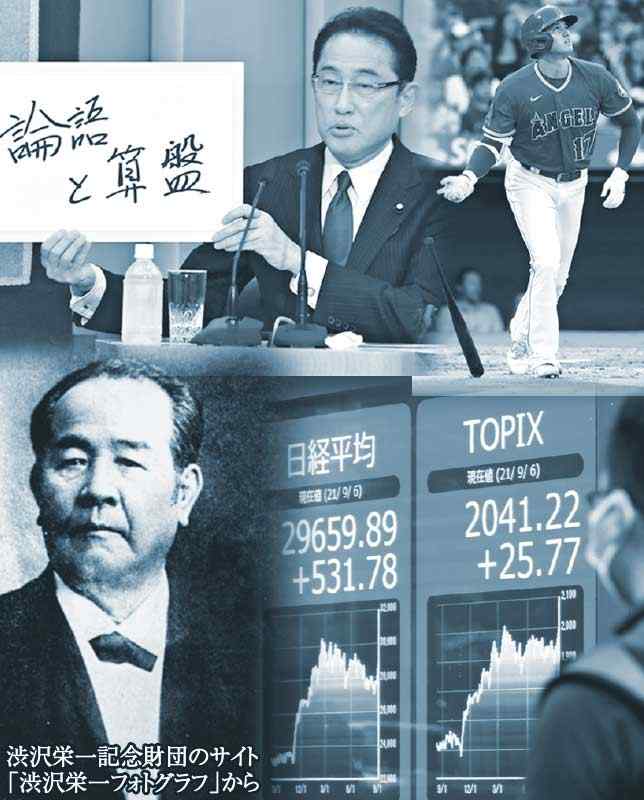

Clockwise from bottom left: “father of Japanese capitalism” Eiichi Shibusawa, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida displaying calligraphy of the title of Shibusawa’s lecture collection “Rongo to Soroban” (The Analects and the abacus), two-way baseball star Shohei Otani, and a display of Tokyo Stock Market data.

12:24 JST, October 7, 2022

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida’s Cabinet has passed the first anniversary of its inauguration with its approval rating on the decline. This series examines how Kishida’s political style so far has affected the handling of key issues and what the future holds for his administration.

***

“I advocate an economic policy of a new form of capitalism,” Prime Minister Fumio Kishida said as he practiced his speech in English on a government-chartered flight from Haneda Airport in Tokyo to New York.

After arriving in the United States, Kishida attended the U.N. General Assembly and gave a speech at the New York Stock Exchange on Sept. 22. He intended to use the occasion to express to investors in his own words his determination to revive the economy.

Before leaving Japan, Kishida called Tetsuya Otsuru, 55, secretary to the prime minister and a former Foreign Ministry official, and other officials of the ministry to listen to his speech and to ask for their advice, such as, “Is this the right intonation?”

Kishida had lived in New York as a child. At the beginning of his speech, he jokingly said, “Maybe you can tell that I have a hint of a New York accent,” to which his listeners responded with laughter.

Having connected with the audience, Kishida invoked the name of Shohei Ohtani, 28, the renowned two-way player for the Los Angeles Angels, saying, “The defining feature of a ‘new form of capitalism’ is that it is a two-way strategy.”

Shift on taxing financial income

The word “sustainability” as Kishida used it in his speech referred to creating an environment for growth by investing funds in measures against climate change and the low birthrate, which cannot be solved by market principles alone.

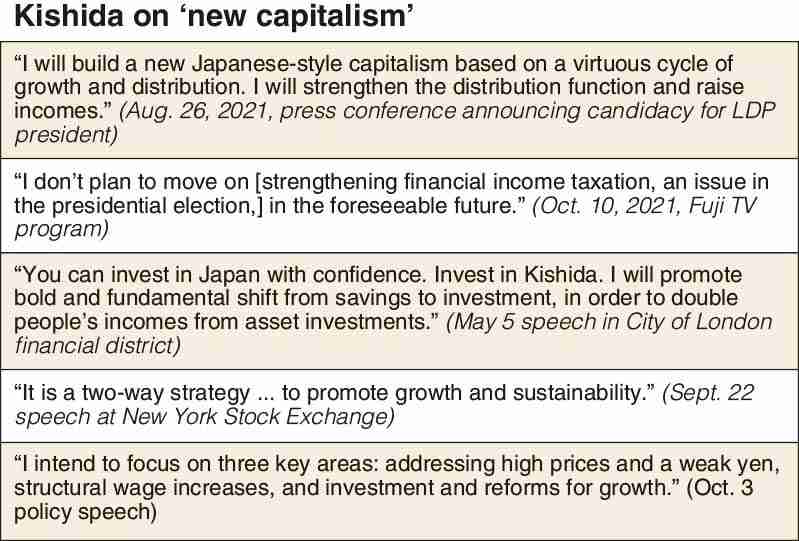

But Kishida did not mention his key phrase, “a virtuous cycle of growth and distribution,” which he had previously used.

Wall Street, where the stock exchange is located, is the world center of capitalism. Thus Kishida thought that “the word ‘distribution’ was not appropriate, as it could be misunderstood as socialism,” a person close to Kishida said.

In his policy speech on Oct. 3, back in Tokyo, he again did not include the word “distribution.”

Since the Liberal Democratic Party presidential election in September last year, Kishida has been struggling to eliminate the negative image projected on his “distribution-oriented” approach as he wants to “dispel the uncertainty in the market.”

Recognizing that economic disparities had widened under the Abenomics economic policy of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Kishida campaigned for the LDP presidency under the slogan of “growth and distribution” to correct the disparities.

Yet, his policy to strengthen financial income taxation for profit from stock sale did not win favor in the market, and stock prices plummeted after his victory in the presidential election in September.

The sharp drop in stock prices was dubbed the “Kishida shock,” and the policy to strengthen taxation on financial income was shelved when Kishida took office as prime minister.

Shibusawa’s philosophy

The “new form of capitalism” first clearly emerged at a Kishida faction symposium in July 2017, but its roots extend much further into the past.

Ken Shibusawa, 61, chairman of an investment management firm and a great-great-grandson of “father of Japanese capitalism” Eiichi Shibusawa (1840-1931), was invited to the symposium.

Eiichi’s philosophy, symbolized by the title of his lecture collection “Rongo to Soroban” (The Analects and the abacus), is that a company’s economic activities (the abacus) should not be driven solely by the pursuit of profit, and should be compatible with morality (the Analects). Ken Shibusawa also inherited this philosophy.

Kishida, an admirer of Eiichi’s philosophy, incorporated it into his policies.

In April 2018, as an economic pillar of the faction’s basic policy formulated in anticipation of his run for the presidency, Kishida stated that he would “realize a bottom-up economy in which small and medium-sized businesses and local regions play a leading role, rather than one that is heavily weighted toward large corporations and the center.” At the time, this was described as a “warm economy.”

Eiichi also left words that point toward sustainability: “Even if an individual becomes a tycoon, [their] happiness will not continue if they are engaged in a business plunging the majority of society into poverty.”

What Kishida has been emphasizing recently instead of “distribution” is “wage increase.”

In his policy speech, Kishida proposed a “structural wage increase.” What he envisions is changing the seniority-based wage structure of companies to a “job-based” wage structure that emphasizes ability, making it easier for capable workers to move to higher-paying companies and industries.

The idea is that this will lead to competition for human resources, which in turn will lead to higher wages. In particular, Kishida seeks to raise the wages of younger generations.

However, should seniority-based wages be overthrown, it could lead to an increase in wage inequality. If this happens, the economy will move further from the ideal of “distribution.”

The philosophy of Kishida’s economic policy is gradually taking shape. Next, concrete actions toward actual results will be required.