Reality of overseas organ transplants / Recipients return to face rejection from medical institutions wary of trafficking

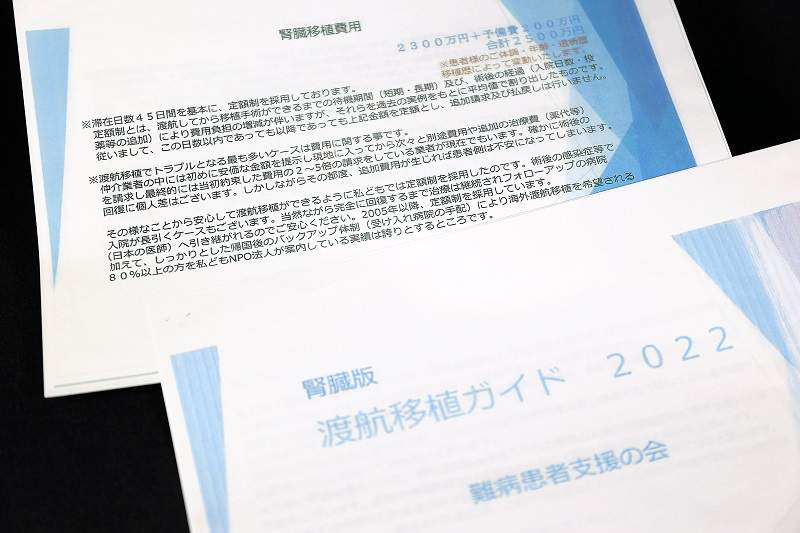

Parts of a pamphlet provided to prospective organ recipients by the Intractable Disease Patient Support Association

20:00 JST, August 30, 2022

Some recipients of organ transplants abroad were refused medical examinations or regular visits to hospitals in Japan, contrary to explanations they had received from a Tokyo-based nonprofit organization that facilitated the surgeries, The Yomiuri Shimbun has learned.

Medical institutions in Japan apparently suspected trafficked organs were used in these patients’ transplants.

The NPO, Intractable Disease Patient Support Association, acts as an intermediary in organ transplants performed overseas.

In one case, a man paid the NPO about ¥18.5 million for an organ transplant and related expenses before leaving Japan for Bulgaria in March 2021. The next month, he underwent surgery for a living donor kidney at a hospital in Sofia. The organ donor was a Ukrainian woman, he said.

The NPO says on its website that once patients return to Japan, they will be introduced to hospitals it designates. The pamphlet for patients also explains that treatment, which will be continued until the patient recovers completely, will be taken over by a hospital in Japan.

According to the man, the 62-year-old director of the NPO told him before he left for Bulgaria that upon his return he would be treated at a general hospital in western Japan famous for its medical transplantation surgery.

However, when an NPO employee contacted the hospital, the institution refused to treat or admit the man on the grounds that he was suspected of having received a trafficked organ.

“I didn’t say anything as they searched for a hospital for me,” the man said. “But I thought, ‘That’s not what they told me.’”

When the man arrived back in Japan at the end of April 2021, the NPO then introduced him to a university hospital in Tokyo, but the hospital refused to admit him. He said the hospital told him that they cannot treat patients who received organ transplants overseas.

The man started going to a different hospital in Tokyo, but was soon denied medical care. He then went to a hospital in Kanagawa Prefecture, but through the course of the treatment, he was again denied medical care. He said the doctor’s attitude changed after revealing he had received a kidney transplant abroad.

Through another introduction by the NPO, the man then visited a hospital in the Tokyo metropolitan area. The institution was reluctant to admit him, but finally agreed to see him after the man pleaded: “I have been refused by hospitals so many times that I have nowhere else to go. Can you help me? It’s a matter of life and death.”

Except for emergencies

In another case, a patient who also received a kidney transplant in Bulgaria around April last year, went to a general hospital in western Japan at the introduction of the NPO but was denied medical care. The patient later found a university hospital in Kanagawa Prefecture to receive treatment.

According to a source related to the NPO, a university hospital introduced by the NPO refused to accept any appointments from a patient who received a deceased person’s kidney in Belarus in July. The patient’s acquaintance then introduced a private hospital and the patient received treatment there.

The NPO’s website has a section on “Treatment after returning home” that says, in part, “in our activities no patient has been left without access to medical care after returning home.”

The Medical Practitioners Law stipulates that doctors cannot refuse the provision of medical treatment without a justifiable reason.

Except for life-threatening emergencies, however, many doctors often disapprove of providing or refuse to give treatment to patients who have received organ transplants abroad.

“If they are found to be involved in organ trafficking, they could face administrative penalties, including the cancellation of their designation as health insurance institutions,” according to a medical specialist.

“It goes without saying that a patient’s life comes first,” said Giichiro Oiso, 47, a lawyer and medical law professor at the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine. “But doctors and hospitals should not be lending a hand to the organ trafficking business.”