At U.N., Micronesia denounces Japan plan to release Fukushima water into Pacific

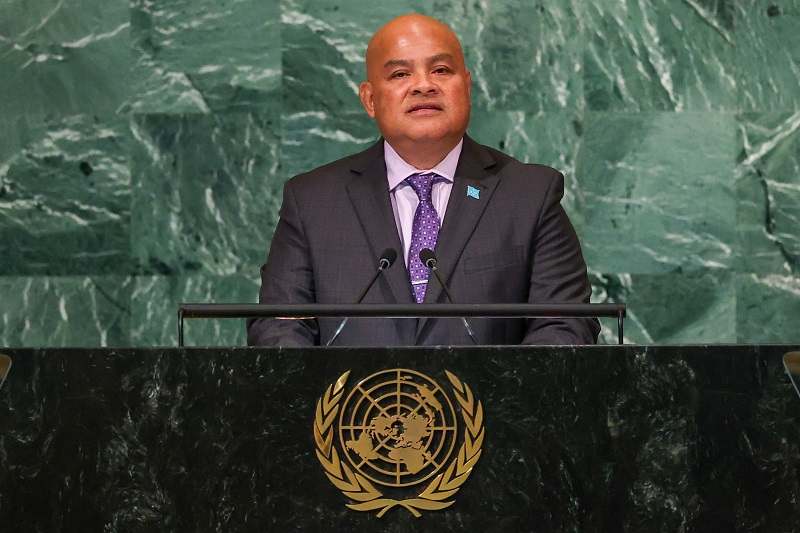

Micronesia’s President David Panuelo addresses the 77th Session of the United Nations General Assembly at U.N. Headquarters in New York City on Thursday.

10:45 JST, September 23, 2022

UNITED NATIONS (Reuters) — The president of the Pacific island state of Micronesia denounced at the United Nations on Thursday Japan’s decision to discharge what he called nuclear-contaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station into the Pacific Ocean.

In an address to the U.N. General Assembly in New York, David Panuelo said Micronesia had the “gravest concern” about Japan’s decision to release the so-called Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) water into the ocean.

“We cannot close our eyes to the unimaginable threats of nuclear contamination, marine pollution, and eventual destruction of the Blue Pacific Continent,” he said.

“The impacts of this decision are both transboundary and intergenerational in nature. As Micronesia’s head of state, I cannot allow for the destruction of our Ocean resources that support the livelihood of our people.”

Japan said in July that its nuclear regulators had approved a plan to release into the Pacific ocean water used to cool reactors in the aftermath of the March 2011 Fukushima disaster.

The water has been stored in huge tanks in the plant, and amounted to more than 1.3 million tonnes by July.

Japan’s Foreign Ministry said at that time that regulators deemed it safe to release the water, which will still contain traces of the radioactive isotope tritium after treatment.

Asked about Panuelo’s statement, Yukiko Okano, the ministry’s deputy press secretary, said in reference to Fukushima that Japan would try its best “to gain understanding from the international community about the safety of our activities there.”

The plant operator, Tokyo Power Electric Company (Tepco), plans to filter the contaminated water to remove harmful isotopes apart from tritium, which is hard to remove. Then it will be diluted and released to free up plant space to allow the decommissioning of Fukushima to continue.

The plan has encountered stiff resistance from regional fishing unions which fear its impact on their livelihoods. Japan’s neighbors China, South Korea, and Taiwan have also voiced concern.

Panuelo also highlighted the threat posed by climate change, to which Pacific island states are particularly vulnerable. He called on geopolitical rivals the United States and China to consider it “a non-political and non-competitive issue for cooperation.”

“For the briefest period of time, it seemed as if the Americans, with whom Micronesia shares an Enduring Partnership, and the Chinese, with whom Micronesia shares a Great Friendship, were starting to work together on this issue, despite increases in tension in other areas,” he said. “Now, they are no longer speaking to each other on this important issue.”

China announced in August it was halting bilateral cooperation with the United States in areas including defense, narcotics, transnational crime and climate change in protest against a visit to Taiwan by U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi.

Panuelo’s remarks coincided with a meeting U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken hosted of the Partners in the Blue Pacific countries, which include Japan with the aim of better coordinating assistance to the region in the face of competition from China.